NIS2: What is it and how should you prepare for it?

A COMPREHENSIVE ANALYSIS

After years of negotiations and drafting between the European Parliament, the Commission and the Council of the EU, the second Network and Information Systems Directive (NIS2) came into force in January 2023. This new legislation follows and replaces the 2018 NIS Directive, broadening the scope of enterprises to which it applies. The aim of NIS2 is to strengthen cybersecurity networks across a variety of sectors in the EU in a harmonised manner. What exactly is changing then, and what measures should be taken in preparation?

NIS1 -> NIS2: What will change?

Who does NIS2 apply to?

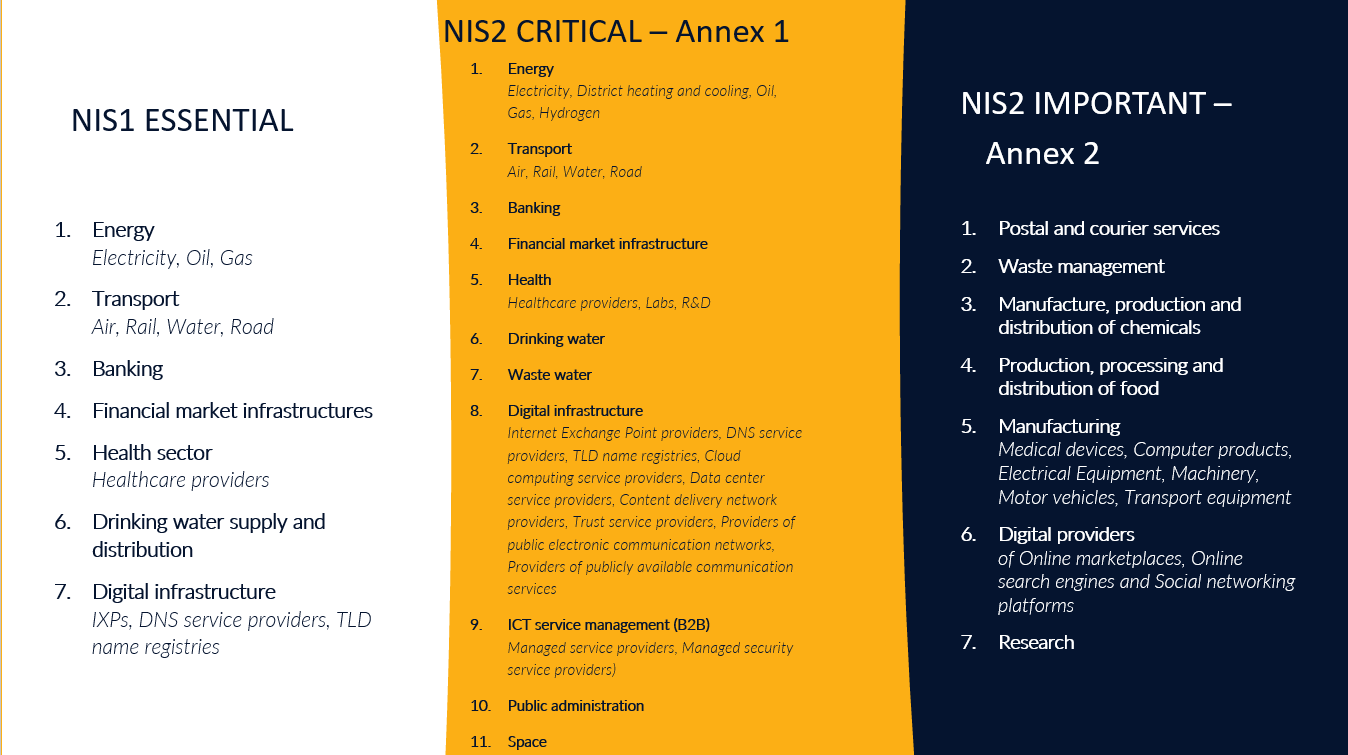

The NIS2 Directive introduces several changes compared to its predecessor. The main goal of these changes is to ensure the security of all organisations that hold a critical position in the functioning of European society. The scope of what exactly constitutes critical is one of the areas that has undergone the biggest transformation. Under the previous NIS Directive, 8 sectors were classified under “essential services”, and Member States were granted significant discretion in the classification of specific services and the implementation of the instrument as a whole. Due to inconsistencies in the interpretation of the first NIS Directive between Member States, and the essentially non-existent enforcement that followed, NIS2 now provides an extended and comprehensive list of 11 sectors that fall under “essential services”, and an additional 7 sectors are marked as “important services,” also subject to regulation. For instance, the pharmaceutical product manufacturing industry and space industry have been added to essential services, while food-production or postal and courier services now belong to the ”important services” category. Subcategories have also been clarified and broadened; cloud computing service providers, data centre service providers, content delivery networks, trust service providers, public electronic communications networks, and electronic communications services are now considered essential within the Digital Infrastructure sector. This means that the number of companies and organisations that NIS2 covers is substantially higher than it has been previously.

However, not all businesses considered to be essential or important services fall under the scope of NIS2. The directive introduced a size-cap under Article 2, ensuring that small and micro businesses are excluded and the smallest businesses falling under the scope of the Directive are at least medium size. According to Article 2 of the 2003 Commission Recommendation on the subject, medium sized enterprises are those employing over 50 persons, and their annual turnover exceeds 10 million Euros. Article 2(2) lists a number of industries and circumstances that are exceptions from this rule, and 2(3) provides the discretion for Member States to include any entities regardless of the size-cap that falls under the essential or important service category.

What measures?

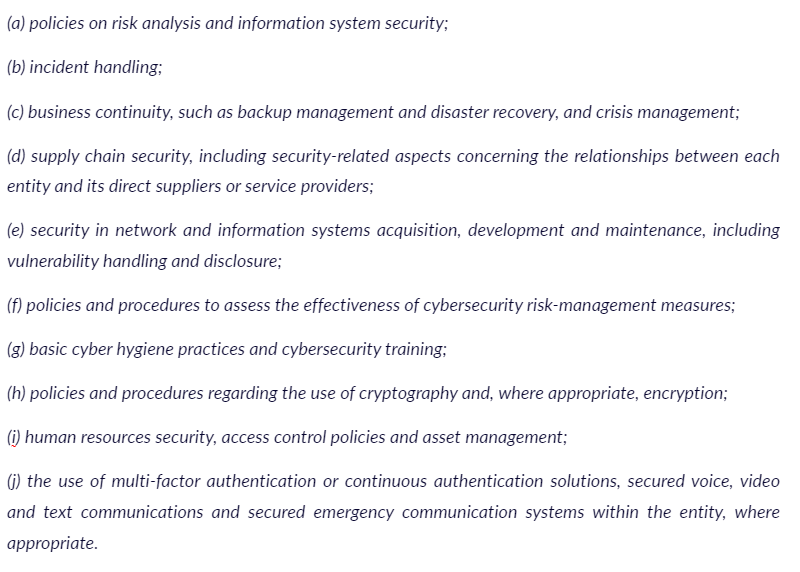

The next, more substantive change brought by the new Directive is a list of 10 cybersecurity measures that will need to be implemented in every organisation and business that falls under the scope of NIS2. This list can be found under Article 21(2). The provision outlines an obligation for Member States to ensure entities adopt the following risk management measures:

Insight from Hunt & Hackett

Before starting to implement the new cybersecurity and risk management measures, keep in mind that they are only a portion of what NIS2 requires from your business. The first step should be to examine the structure of your business and management so there is a proficient setup to fall back on. Your managing body has to be able to handle strict incident response and reporting requirements, which may call for significant reorganisation of security monitoring, incident response, and processes & infrastructure. See more on this in the following section.

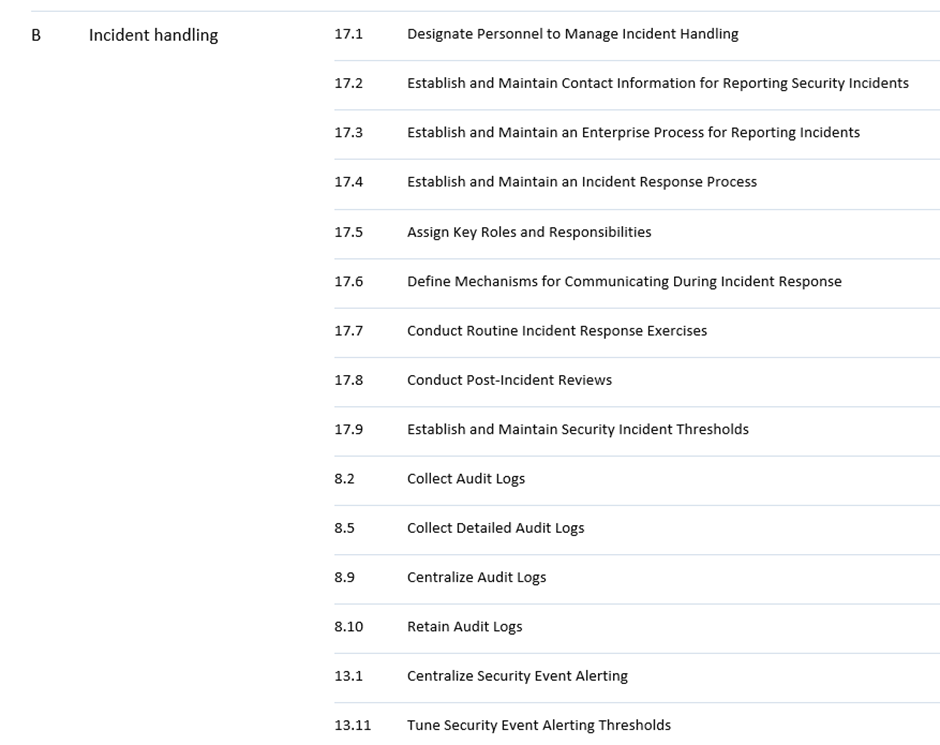

Those familiar with the technical aspects of cybersecurity measures will notice that the risk management measures laid out by the Directive largely overlap with the Center for Information Security (CIS) framework.

At the time of writing it is still unclear what underlying security controls the NIS2 risk management encompasses, as there is no reference to specific security controls or reference to an underlying framework such as ISO 27001, ISO 27002 or CIS controls. This means that it remains somewhat unclear what is required under NIS2. Hunt & Hackett has decided to focus on what we do know and started mapping the requirements with the CIS controls that issued in our Security Program Gap Assessments. This way a view is created on what is likely to be required to comply with NIS2.

For instance, incident handling in NIS2 Art.21(2)(b) largely overlaps with CIS control 17 Incident Response Management, although the more broad wording of NIS2 allow for additional measures, which is why some aspects of CIS control 08 Audit Log Management, and CIS control 13 Network Monitoring and Defence may also be required to be implemented by the Directive. Furthermore, basic hygiene practices under Art.21(2)(g) could potentially include close to all measures. Hunt & Hackett created a mapping of all NIS2 requirements to all CIS controls for easier navigation. This self-assessment tool can help your organisation to prepare for NIS2 compliance.

You can find our NIS2 to CIS mapping tool below:

Besides the NIS2 to CIS mapping tool, we've also created a NIS2 to ISO27001 & ISO27002 mapping tool.

NIS2 - to - CIS:

An Example

These measures under NIS2 should always be appropriate to the risks posed to the specific sector or business, depending on the business’ exposure to risk, its size, the likelihood of incidents, and the severity of incidents from a societal and economic perspective, which leaves a high degree of subjective judgement to the individual conducting the assessment. One point often emphasized throughout the Directive is the strengthening of supply chain security in order to guarantee that the relationship between the business in question and its suppliers or service providers is well defended. Digital industries also fall under stricter regulations according to Article 21(5), but the exact conditions are not yet known. The Commission has until 17 October 2024 – the exact deadline for Member States to implement the NIS2 Directive – to adopt additional acts specifying technical and methodological requirements of the measures listed earlier when it comes to businesses operating in the following sectors: DNS service providers, TLD name registries, cloud computing service providers, data centre service providers, content delivery network providers, managed service providers, managed security service providers, providers of online market places, of online search engines and of social networking services platforms, and trust service providers.

Are there any additional changes?

In case the scope assessment’s result is in the affirmative, that means that the measures set out by the Directive apply for the given business or organisation. There are additional factors to be taken into account, such as Member State’s ability to excuse certain businesses or agencies operating for instance in the national security field. Overall, however, the assessment will give a firm implication whether the regulated security measures need to be implemented.

Next, as mentioned, there is an emphasis on supply chain related matters in the Directive, particularly on ICT supply chains and supplier relationships. This means that businesses originally falling outside of the scope of the instrument could potentially become obliged to follow its measures due to their ICT supply chain connections. The exact measures required are not yet known, as the directive merely instructs Member States to enact policies to ensure the cybersecurity of ICT supply chains.

Another, more specific new requirement laid down by NIS2 relates to management bodies. Every organisation that falls under the scope of NIS2 is required to have their management to approve risk management measures and oversee their implementation. Under Article 20 of the Directive, the approving managing body can also be held liable for potential infringements. To prevent this, members of management bodies are required to undergo risk management and cybersecurity training. Additionally, Hunt & Hackett’s Security Program Gap Assessment (SPGA) may prove useful when navigating risk management. In our SPGA approach, which has now been tailored to the new NIS2 requirements, we use the threat landscape as the basis for defining security controls to control risks to an acceptable level.

While this aspect of the new directive has not attracted much attention or debate so far, the relative unclarity of the wording of Article 20 is important to point out. The term “management body” is usually meant as an umbrella term referring to the overall governing and decision making functions within a firm. Whether NIS2 requires all employees with potential decision making authority to follow trainings, or a specific NIS2 compliance body should be appointed, needs clarification.

The last upcoming changes putting additional obligations on companies and organisations relate to their incident reporting requirements. Article 23 of the Directive lays down these requirements, although in a rather vague manner. According to the provision, all entities falling under the scope of NIS2 and experiencing a significant incident will have to notify the national computer security incident response team (CSIRT) or other competent national authorities without undue delay, as well as the potentially affected recipients of their services. In practice, notification to the national authorities will be required to have a three step procedure. First, within 24 hours of becoming aware of a significant incident, an initial report has to be filed. This report needs to indicate whether the incident is suspected to have been caused by a malicious actor, and whether it has any potential cross-border impact. Within 72 hours of the incident, a follow-up report needs to be submitted with any updates, detailing the incident’s severity, impact, and any compromise. A final report needs to be submitted within one month of the incident, including “(i) a detailed description of the incident, including its severity and impact; (ii) the type of threat or root cause that is likely to have triggered the incident; (iii) applied and ongoing mitigation measures; (iv) where applicable, the cross-border impact of the incident.” Depending on how much detail authorities will require in practice, one month to prepare a thorough incident report of a serious security incident is extremely short.

In order to restrict the volume of reports inevitably streamlined towards national CSIRTs due to the expansion of the directive’s scope, NIS2 requires only significant incidents to be reported. An incident can be considered significant if it has or is capable of causing severe operational disruption or financial loss, or if it has or is capable of affecting other persons or entities by causing either material or non-material damage. While this definition seems detailed at first glance, it soon becomes obvious that incidents falling under its scope are not only what would colloquially be considered significant. For instance, a strict interpretation of the text would suggest that any financial loss needs to be reported, with no minimum amount of damage. “Severe disruption” is highly subjective and leaves a lot of discretion to the decision maker. Lastly, even a single phishing email would be “capable of affecting (…) persons by causing considerable (…) damage.” How these requirements will be implemented and enforced, remains to be seen.

The list of changes brought by NIS2 and detailed above is not exhaustive, and some additional developments lay down requirements directly to the Member States to implement rather than companies and organisations. The most noteworthy changes are states’ obligation to supervise cybersecurity measures in the essential and important sectors, enhanced focus on enforcement, cross-border cooperation, and information sharing between states. It is therefore predicted that, unlike its predecessor, NIS2 will, in fact, have a meaningful effect on European safety and cybersecurity.

Actionable Steps

Regardless of the risk assessment, however, some actionable steps can already be taken in preparation for the incoming legislation. For instance, it is worth setting up internal managerial groups specifically focused on compliance, and start exploring cybersecurity training options available on the market. In case a cybersecurity incident is detected in the company’s or organisation’s network, rigorous reporting obligations will need to be met, and therefore arranging an internal system for reporting is advisable. It is important to keep in mind, however, that both the sector- and business-specific risk assessment from a cybersecurity perspective, and incident reporting are complex tasks requiring a high level of expertise, which is why it is highly recommended that entities falling under the scope of NIS2 but without an advanced security department look for cooperation with external cybersecurity experts.

Current Trends

While the NIS2 Directive is yet to be implemented in EU Member States, cybersecurity has been playing an increasingly important part in organisations and entities in recent years. This is partly due to existing legislation such as the original NIS Directive or the EU Cybersecurity Act, but also due to high profile attacks on prominent institutions, such as the interference with the 2017 French election campaign, the 2019 attack on Maastricht University, or the numerous attacks on Ukrainian governmental agencies and the energy sector during the war in Ukraine. This non-exhaustive list of events have highlighted the need for strengthened security.

Multiple factor authentication has been a popular way to protect networks on the user’s side. Banks, for instance, require confirmation on our banking apps when making significant transactions, Gmail often instructs users to confirm their identity on a different device when logging in from an unknown IP address, and logging into our personal Dutch governmental accounts is only possible with SMS- or app-confirmation. Lately, more and more universities are opting for this procedure as well. The tendency is clear, but there is still a long way to go before ideal security is achieved.

Criticism

Despite the goal of the Directive is to strengthen cybersecurity in the EU, its success is not yet certain. Its predecessor, the first NIS Directive, certainly failed its purpose. After its 2018 final deadline for implementation, it quickly became obvious that countries interpreted it in vastly different ways, and it was virtually unenforceable. To address its vagueness and lack of coordination, NIS2 draw up stricter and clearer requirements. However, whether these new requirements will actually achieve what they are supposed to, is still a question. With stricter interpretations comes the issue of fitting new and emerging technologies and sectors in the scope of the instrument. By the time states need to implement the directive into their domestic legal framework, major technological advancements can, and will probably take place. It is not yet clear, for instance, how exactly the recent AI-boom will affect the cybersecurity sector, but there certainly is a chance that it will. Frequently amending the directive will not only cost time and resources on an EU-level, but it will also create legal uncertainty for companies, organisations, and everyone potentially falling under its scope. Additionally, the scope itself may provide issues in the future, as what is considered an essential or important sector in our society will probably keep changing, just as it has changed since the implementation of the original directive.

Additionally, it is worth noting that under NIS2, persons in the managerial body will become directly liable for the consequences of cyber-incidents. While this provides incentives for more thorough decision making, it is questionable whether corporate liability would not be more efficient, especially considering that cybersecurity measures are often outsourced. This issue has created a rather significant contention since the adoption of NIS2.

On the more technical side, there is also criticism to be found regarding the content of the NIS2 Directive. For instance, the timeline for reporting obligations may be too short. The first report after the incident needs to be submitted within 24 hours of its discovery. This would require organizations to have Incident Response (IR) retainers in place in order to have an initial investigation performed in such a short time frame, unless the organisation has an in-house CSIRT team. NIS2 also requires a final report to be submitted no later than one month after the discovery of the incident. However, major incidents often require months of forensic analysis and investigation. Therefore, the report after one month would most likely be non-complete and lacking useful insight. Moreover, requiring three different reports within a one month period regarding the same incident could place an undue burden on companies trying to focus on resolving the issue itself. In other words, NIS2 brings stringent requirements to the logging of data sources (the industry norm is selective rather than exhaustive due to the associated costs), the forensic capabilities of active security monitoring (such as with Managed Detection Response (MDR) or in-house SOCs) and Incident Response labs in order to significantly reduce processing time. This, of course, is not the case for the majority of organisations outside of the security sector and would imply a significant overhaul of the security architecture.

In general, these time frames are only realistic when extensive logging and active monitoring with forensic analysis capabilities are in place. This links to Hunt & Hackett’s IR readiness assessments that looks into both the technical and organizational aspect. Without such preparation, it is close to impossible for organizations to meet the required timelines as typically there is no data to answer these questions. The requirements will also affect MDR solutions; it is desirable to have a solution that ingests significant logs and is not selective, since it is not known what data is needed for forensics and is designed from a forensic analysis perspective. This, however, goes against the current market trend which is very selective on data ingestion due to volume based pricing, and it often correlates alerts and not underlying logging data. Consequently, this will hamper follow-up forensic analysis from the SOC.

Conclusion

The NIS2 Directive aims higher than its predecessor by broadening its scope and implementing more comprehensive requirements. Entities falling under its scope will have to put a series of yet undetermined cybersecurity measures in order to comply, as well as to set up internal mechanisms to be able to handle incident reporting, management body obligations, and more. The Directive is not without its flaws from a practical perspective, but clarifications are expected once Member States start rolling out their respective national legislative instruments. In the meantime, it is crucial for companies to start conducting an assessment to determine whether NIS2 will apply for them, and if so, prepare in time for the upcoming cybersecurity requirements.