The Definitive Guide to Ransomware

“Ransomware is a type of malicious software designed to block access to a computer system until a sum of money is paid.”

– The Oxford English Dictionary

“Ransomware is a type of attack where threat actors take control of a target’s assets and demand a ransom in exchange for the return of the asset’s availability and confidentiality.“

– European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA)

1. What Is Ransomware?

1.1. Introduction to Ransomware

As exemplified in the quotes above, the term ransomware has several characterizations, placing the focus on different aspects of the attack. While ENISA defines it as a type of attack, ransomware usually refers to the malware used during the attack. The common aspects across different organizations, cybersecurity companies, and dictionaries taking up the task to define ransomware usually include the malicious software deployed and a ransom note demanding financial gains in exchange for access being handed back to the network’s operator. However, these definitions do not cover all types of ransomware attacks; while the ransom is often money, it could be political demands or other types of actions as well. For instance, in 2017 Palo Alto researchers discovered a campaign demanding public political statements of their targets, which would include the incitement of violence against an unnamed Middle Eastern political leader.[1] Some attacks do not even include a ransomware note – should the malware used still be considered ransomware? In this analysis, the full spectrum of ransomware will be explored, with special attention to the outlier cases.

In general, ransomware can be distributed randomly or in a (semi-)targeted manner. The latter can be aimed at either individuals, or to specific businesses, organizations, or government agencies. Ransomware attacks, and targeted ransomware in particular, can result in serious consequences for the victim, such as the disruption of operations, financial losses, or the loss of sensitive or proprietary information. The motivations behind these attacks vary, but most often the attackers are seeking to extract a large sum of money from the victim. In some cases, the attackers may also be motivated by political or ideological goals, such as causing disruption or destruction.

During a targeted ransomware attack, the victim usually experiences unauthorized access to their network, the encryption of their data, and the display of a ransom note demanding payment. Disruption to the targeted business or organizations’ operations is also common. In these cases, the victim experiences inability to access or use certain systems or data. This is why it is crucial for businesses, organizations, and government agencies to have an extensive set of cybersecurity measures in place in order to prevent and mitigate the risk of a targeted ransomware attack as well as be able to recover from a ransomware attack with minimal disruption to their business.

1.2. Ransomware Actors

The attackers in ransomware attacks come in all shapes and sizes. They can be well-organized and even state-funded Advanced Persistent Threat (APT) groups, politically or socially motivated hacktivist teams, or even bored individuals with questionable moral standards looking to stir chaos and gain financial advances. Some of them focus primarily on ransomware attacks, while others specialize in, say, espionage, but occasionally engage in ransomware attacks. Do we still call them ransomware actors? Regardless of these questions, however, ransomware attacks tend to draw a lot of attention even outside of cybersecurity circles, which contributes to a variety of institutions and organizations monitoring them and tracking their actions. This results in a large number of data sets and statistical analyses circulating on the internet published by security companies, ICT businesses, government agencies and more. Interestingly, the numbers and conclusions in these publications often do not neatly align with each other . Nevertheless, some general trends and estimated figures can be concluded from the varying reports.

Most research organizations put the number of active ransomware groups at around a hundred. Microsoft revealed in 2023 that they are monitoring “more than 100 ransomware gangs,”[2] which aligns closely with Hunt & Hackett’s current tracking of 97 individual actor groups. Contrarily, in a 2022 ENISA report it was stated that only “at least 47 unique ransomware threat actors” were identified by them.[3] This discrepancy is most likely due to selection bias, as researchers only included actors with at least 5 incidents.[4] Such a method helps filtering out the occasional ransomware users, but provides a narrower picture when evaluating possible threats a business or organization is facing. ENISA’s approach effectively ignores half of all the actors potentially posing a risk. Another factor making the determination of an exact number difficult is that there are alliances with affiliates that perform specific tasks within the ransomware supply chain. Without a global consensus as to whether we count each affiliate as a group, the number of ransomware groups will remain a rough estimate.

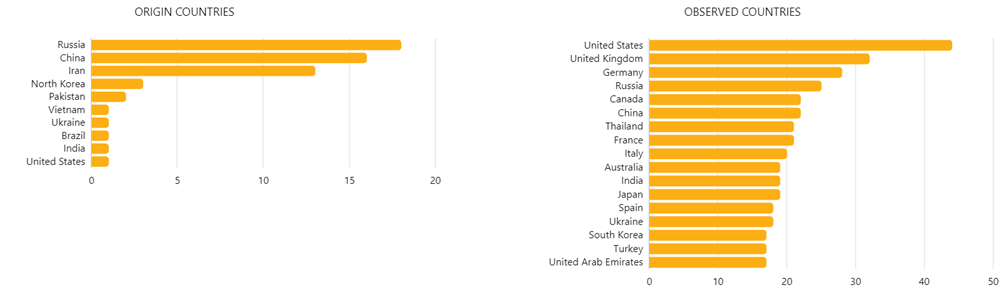

When a ransomware attack takes place, it is not always obvious who is behind it. Often times, attacks and the malware used remain unattributed to any specific known or emerging group. Based on the available information Hunt & Hackett has compiled, Russia, China and Iran have the highest number of groups operating in the business of ransomware. Even though their main targeted countries vary, and social and political events often change the dynamics, in general the United States, the United Kingdom and Germany experience the highest number of attacks.

Most active ransomware groups in 2022

Source: Ransomware Report 2023: Targets, Motives, and Trends | Outpost24 blog

As mentioned above, there are an undetermined but huge number of actors active in the ransomware field. Depending on their tracking focus, cybersecurity researchers often identify the most dangerous or prolific ones in different terms. For instance some APT groups, such as APT29, are very well organised and conducting a disproportionately large number of attacks – including ransomware – and yet they often do not appear on the top of the list when it comes to ransomware actors due to their primary engagement in espionage. There are a handful of groups, however, that are hard to ignore. Let's get to know two of them a little deeper!

- Conti Group — One such actor is Conti Group, notorious for its aggressive tactics and associated with the Conti malware. They are believed to be the same as the group tracked as Wizard Spider. Conti Group employs between 60 and 100 people, operating as a business – with departments and employees often not being aware of the criminal activities the organization is conducting. By 2020 the group had become the third most active ransomware groups.[5] By 2022, they had attacked at least 700 victim organisations worldwide. [6] Contrarily to BlackCat, Conti does not sell the stolen data on the dark web, only conducting business with their trusted affiliates. In 2022 the group hit cybersecurity headlines when one of their members published 60.000 internal messages dating January 2021 until February 2022. The action was triggered by a statement made by the group’s leaders expressing support for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The person behind the leak is believed to be of Ukrainian origins, condemning Russia’s actions. The leaked messages provide a window into one of Russia’s most active APT groups, revealing its hierarchical structure, employee payments, and their internal tools. Researchers reviewing the messages revealed that among the top priorities of the operation was to keep employees satisfied and the workplace spirit high. Three months after the leak it was reported that Conti shut down its operations. It is theorised that the leak was the reason for this, although it has not been confirmed.[7] It has been reported that by early 2023, members of the original Conti gang rebranded themselves in three separate, smaller groups. These have been named Black Basta, BlackByte and Karakurt.[8] Black Basta and Karakurt were listed among the most active ransomware groups in the second and third quarters of 2022 identified by TrendMicro.[9]

- BlackCat Gang — Another well-known actor is BlackCat Gang, also known as ALPHV. As it often happens, this group also shares its name with the malware they are most known for: BlackCat. The group’s origin country is not confirmed (although they are believed to be Russian), and they are not focusing on a geographical area as their target either.[10] The group was discovered in late 2021, which makes them one of the newest members on the ransomware scene. It has been speculated that they are associated with other APTs, such as Conti, DarkSide or BlackMatter.[11] BlackCat Gang gained notoriety due to their sophisticated tools and techniques. They were only one of the first groups known to be using the Rust programming language which gave them an advantage in avoiding detection.[12] The unpredictable nature of the operations of BlackCat Gang also stems from the fact that they are utilizing the Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS) structure, essentially breaking down the attack into phases. Their attributed attacks include OilTanking GmbH in Germany, Swissport, which is an aviation company, the University of North Carolina and the Florida International University.[13] Typically, they would demand 2.5 million USD payment for restoring the encrypted data.[14] In December 2022, BlackCat attacked Colombia’s largest energy supplier EPM, disrupting their services. The ransomware note used during the attack has been reported to be a template note used in all BlackCat operations.[15] The group keeps an extensive list of breached entities on their website, which is also the place they release stolen information. This centralised structure makes them particularly effective as the information is easily accessible. In 2022 NJVC, an IT company associated with the US Department of Defence, was added to the list, but the breach has not been confirmed. [16]

These actors only represent a small portion of all groups conducting ransomware attacks around the world, but their diverse nature shows how widespread and unpredictable the attacks can be.

1.3. Actor Motivations

The obvious and most common motivation behind ransomware attacks is, of course, financial gain. In these attacks, the actors encrypt files on the victim’s device, display a ransom note demanding money, and provide instructions on the transfer. In order to maintain their anonymity, attackers increasingly demand the payment in Bitcoin or other cryptocurrencies. Depending on the actors, cyber-attacks in general can be conducted based on a variety of motivations such as intellectual property theft or reputation damage.[17] Within the world of ransomware financial motivation is still the most common, but espionage, destruction and other non-monetary goals are rapidly increasing. While the overall number of ransomware attacks has been rising steadily, between 2010 and 2016 the share of financially motivated ransomware attacks decreased from around 90% to around 70%.[18] Even when the aim of the attack is monetary gains, the actors’ approach has been evolving; hospitals, schools and other critical infrastructure with limited resources are often targeted because of the highly sensitive data they need access to, and the consequent huge impact of data loss.[19] Non-financial gains primarily include destruction and espionage. In these cases, the aim of the attack is to sabotage the operation of the victim, cause chaos, or gain access to critical information. While information theft and espionage can be conducted without encryption and ransom notes, the theatrics of ransomware attacks guarantees a larger volume of media attention. In 2022, Chinese group Bronze Starlight were conducting ransomware attacks, but researchers identified the activities as masked cyber-espionage operations.[20] The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency of the US concluded in a report that the financial gains of North-Korean state-funded ransomware attacks are often tunnelled directly back to fund their espionage activities.[21] Furthermore, in an interview with Talos Intelligence Group, a Russian hacker only referred to as Aleks stated that he, as an individual, turned to conducting ransomware attacks after the perceived lack of recognition from businesses he had notified about their vulnerabilities.[22]

Although ransom originally means “money that is paid to […] free a person […],”[23] ransomware demands could potentially be actions instead of money as well. Just as criminal groups can demand political action by taking someone hostage, cybercriminals can threaten to disclose or sell sensitive information in an attempt to bring about political change. Security initiative The Alliance for Securing Democracy (ASD) theorises that technological tools such as ransomware could soon become valuable to demand political statements or release of prisoners.[24] Although this exact type of ransom demand is not yet precedented, groups are often politically and ideologically motivated. This includes state-sponsored actors such as North-Korean or Russian APTs, as well as hacktivist groups such as Anonymous.

As seen, the motivation behind attacks depends on the actor, but most often the main goal of ransomware operations is still financial gain. Nevertheless, ransomware tools are increasingly used for destruction and espionage purposes as well.

2. How Does Ransomware Work?

After getting acquainted with ransomware actors and the motivations behind their attacks, the following chapter will delve into the intricate workings of ransomware, exploring its mechanisms and some notorious cases that have left lasting impacts on organizations globally. The chapter begins with an analysis of two significant ransomware incidents—WannaCry and the Colonial Pipeline attack—describing operations of the threat actors and the repercussions faced by the victims. The focus then will shift to localized incidents, emphasizing that ransomware is not limited to major corporations but can also target smaller entities, as exemplified by the Gemeente Buren municipality in the Netherlands. The chapter also introduces readers to the typical phases of a ransomware attack, shedding light on the modus operandi of threat actors. Furthermore, it explores the diverse variations of ransomware, ranging from Crypto and Locker ransomware to Double Extortion, Doxware, and the emergence of Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS).

2.1. Famous Ransomware Cases

Ransomware comes in different forms. The best way to understand how an attack works and the impact it can have on an organisation is to dive into a few well-know cases. The incidents examined in this chapter unveil the multifaceted challenges organizations face, emphasizing the critical importance of proactive cybersecurity measures in the battle against evolving cyber threats.

- WannaCry — One of the most prolific deployments of ransomware was the 2017 WannaCry attack launched by North-Korean group Lazarus. While the group is not primarily known for ransomware attacks, they are state-sponsored and well-organised, which allows for the use of a large variety of malware. During the WannaCry attack, more than 200.000 devices were affected in at least 150 countries.[25] The attacks used a cryptoworm, making it possible for the malware to spread itself across computer networks. Although the Microsoft vulnerability that was exploited had been identified in advance, and a patch had been released, the update was not mandatory, leaving networks vulnerable. According to Kaspersky Lab, 98% of affected computers were using Windows 7.[26] Organisations across all sectors were affected, but UK’s National Health Service was hit especially hard. The attacks forced health services to halt for a day, operating on an emergency-only basis.[27] The spreading of the malware was brought to an end when 22-year-old British security researcher Marcus Hutchins discovered a built-in kill switch. The malware required an unregistered domain, which then Hutching registered for a DNS sinkhole[28] in a move which has been referred to as saving the internet.[29] WannaCry is technically still considered to be active, but the decryption key is available.[30] The attacks were not particularly successful from a financial point of view; the group only received around 100.000 USD in payments. However, the damage caused by the attacks is estimated to be between hundreds of millions and 4 billion USD worldwide.[31] This, and the fact that no decryption code was provided even upon payment, indicates that the primary motive behind the worldwide WannaCry ransomware attacks was, in fact, not financial. Hunt & Hackett tracks Lazarus, the group believed to be behind WannaCry, as mainly operating for destruction, espionage and financial gain. Although a relatively small amount of payments was collected by the group during the WannaCry attack, they have since upped their game and are believed to have stolen over 3 billion USD over the last six years. Lazarus has been observed to target both public and private entities on every continent. What is characteristic to their operations – although similarly to other APT groups as well - is the usage of Command and Scripting Interpreters during the execution phase of the attack, and a variety of Defence Evasion techniques such as Indicator Removal, System Binary Proxy Execution, Masquerading and Obfuscated Files or Information.

- Colonial Pipeline — In May 2021 the news broke that US oil pipeline system operator Colonial Pipelines was under a cyberattack. Pictures and videos were circulating on social media of people pouring gasoline into plastic bags and other unsafe storage devices. While the content was proven to be false – or rather, recorded years earlier,[32] - the attack that triggered the panic over gas shortages was very real. A group later identified by the FBI as Russian criminal gang Darkside[33] conducted a ransomware attack on Colonial Pipelines, the largest pipeline system in the United States[34] supplying 45% of the East Coast of the US with gasoline.[35] The attacks forced the enterprise to temporarily shut down all pipeline operations and most of their IT systems.[36] It took six days for all operations of Colonial Pipeline to resume. This quick resolution for such a disruption would idealy indicate the expertise of the incident response and cybersecurity experts involved. In this case Colonial Pipelines however did pay the demanded 4.4 million USD ransom amount. According to the company’s CEO, this was because the extent of the intrusion was unknown at the time, and therefore they opted for a quicker resolution.[37] The financial blow was softened for Colonial Pipelines within a month, wben an FBI operation (triggered by a notification by Colonial Pipeline) led to the seizure of 2.3 million USD worth of the Bitcoin payment.[38] After the attacks, the company implemented multiple changes in their cybersecurity infrastructure, appointed a Chief Information Officer, increased their investment in tech infrastructure and cyber security by 50%, and dedicated 1 in 4 employees to technology.[39] Interestingly, their website is now only available from North-American IP addresses, although this is easily circumvented by the use of VPNs. The attacks had broader implications to cybersecurity on the national level as well; the CISA launched the Joint Ransomware Task Force together with the FBI, and established the Joint Cyber Defense Collaborative[40] in order to “develop strong strategic and operational alliances within the cybersecurity community.”[41]

- Gemeente Buren — Serious ransomware attacks involving high payment demands not only happen on a global scale or to billion-dollar companies. In April 2022, the municipality of Buren in the Netherlands – home to a little over 270.000 residents - suffered a ransomware attack, encrypting 12 of their systems.[42] For a detailed report on the attack and the subsequent research conducted by Hunt & Hackett, visit our Red Mudnester Rapportage. The shorter version is that the municipality’s network was originally infiltrated through a VPN supplier user account. After initial access, the attackers used Remote Desktop Protocol to connect to file shares and domain controllers. It has been established that initial access took place in January 2022, which means that the actors were inside the system for close to three months. Going unnoticed and undetected, even when anti-virus software alerted Cobalt Strike, allowed them to collect a large amount of data. By the time the ransom note was displayed and the files were encrypted in April, the actors claimed to have stolen five terabyte worth of information.[43] The municipality had offline backups of the majority of the stolen data, which made complying with the attackers’ ransom demands a less appealing as it appeared that the municipalities systems could be restored. The counter move by the attackers was that they they eventually leaked 130 gigabytes of information as a sample, in order to prove that they were, in fact, in possession of the data and to prove that they could still hurt their victims. What exactly led the attackers to the municipality of Buren cannot be determined, but it is most likely that the attack was based on opportunity. This is corroborated by the fact that both the ransom note and their publication on their dark web forum refers to the municipality as a company, indicating a lack of background research into their target. For more information on this specific attack, read our Red Mudnester report, or the last chapter of this Pillar Page.

- Maastricht University — Another highly publicized attack conducted against a Dutch public institution is the 2019 ransomware attack on Maastricht University’s network. On 23 December 2019 critical systems within the infrastructure of the university were encrypted with clop-ransomware, which caused the shut-down of the institution’s critical systems. The attackers demanded Bitcoin payment in exchange for the decryption key. Even though the university was operating with significantly reduced staff due to the Christmas break, security company Fox-IT was called in the day after, and the management of the institution began a week-long decision-making process. The university had to weigh their options of giving in to the attackers and using their funds from governmental and private funding and tuition fees to pay the ransom, or waiting to see whether a decryption key could be created and risking the disruption of education and welfare of students. On the 30th the university decided to pay roughly 200.000 EUR in Bitcoin to the attackers. This enabled exams to be held without delay, and education could resume in January as planned. After an analysis, the investigators determined that the attackers, later identified as potentially Ukrainian or Russian TA505 group, gained initial access to the network via two phishing emails opened on the 15th and 16th of October. Both emails were written in English, which would not raise an alarm immediately in an institution with 50% of their student body coming from abroad.[44] The first email contained a link to an attachment which the receiver was supposed to sign, while the second one masqueraded as a thank you email from a student for helping her find housing. Considering the fact that the housing crisis has been a huge obstacle for residents of the Netherlands, and international students in particular, it seems that the attackers conducted at least some reconnaissance. While the email had been flagged a couple of times, the link in the email was continuously changed and eventually someone in the network clicked on it. In November, the attackers obtained full rights in the network through a server that was lacking the necessary security updates. The lack of detection when anti-virus was disabled did not help either, and therefore the attackers were able to move through the network and obtain credentials, without ever being detected. It is believed that the attackers only collected data of the “topology of the network, usernames and passwords of multiple accounts, and other network architecture information,”[45] but not any additional sensitive information. Although the attack most definitely caused chaos, imposed financial losses to the university and inconvenienced its students and staff, not all consequences of the attack were negative. Maastricht University was fairly transparent throughout their handling of the incident, which led to news headlines, a national conversation, and other universities implementing new, precautionary cybersecurity measures. On top of that, it was announced that in February 2020, the Netherlands Public Prosecution Service (OM) managed to seize a Bitcoin wallet containing a portion of the payment the university made in 2019.[46] Due to the change in Bitcoin’s value, it is estimated that by mid-2022 – when the cryptocurrency was still in the OM’s possession – it was worth over half a million Euros.[47] This would mean that even after counting for inflation, the university would receive more funds than it paid. While this is most definitely a welcome development by the institution, this sum of money will not be able to compensate the additional expenses and disruption in education that the attacks cost. It is therefore imperative to keep in mind that even from a financial point of view, the best decision an organisation can make is to prevent a cyber-attack.

2.2. A Typical Ransomware Attack

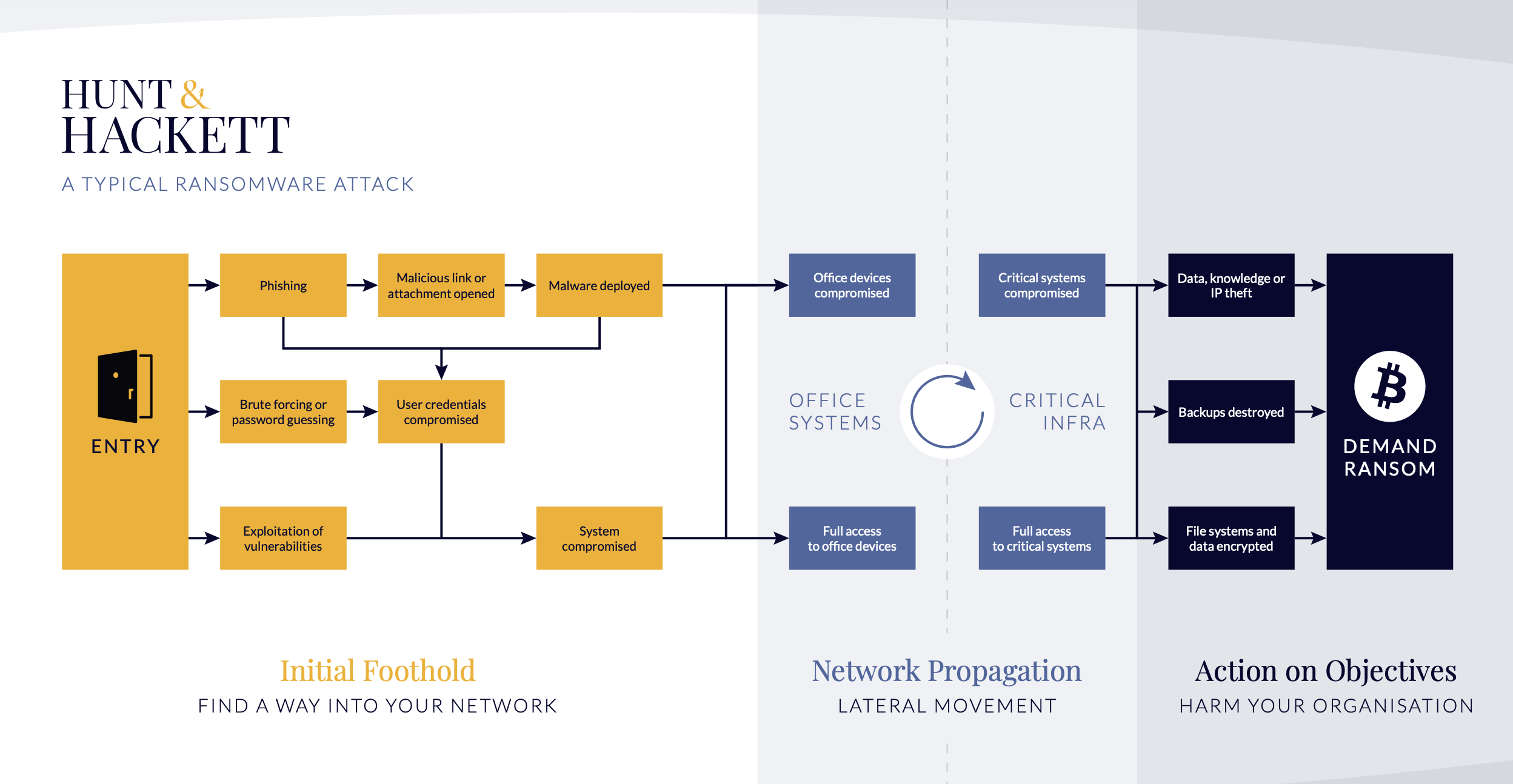

Groups that have been observed to engage in ransomware attacks tend to use a wide variety of techniques, but Phishing, using Command and Scripting Interpreters, Obfuscating Files or Information, enticing User Execution and using Encrypted Channels are among the most utilized methods. The picture above shows the phases of a typical ransomware attack. This includes the initial foothold phase, during which the attackers gain access to the targeted network and start establishing their presence. During the next phase, network propagation, the attackers gain access to more devices or even the whole infrastructure. The last phase – action on objectives – is what is commonly thought of as the attack itself. This is when the attackers conduct the actual information theft, encryption of files, destruction, or all of the above. These moves then allow them to demand ransom from the organization in exchange for the stolen or encrypted data. However, it is worth noting that this is only one way of conducting a ransomware attack, and more variations have been continuously emerging. For instance, triple extortion attacks would involve additional steps, most often DDoS attacks and publication of stolen data. The following section will explore the different variations to better understand how ransomware attacks can play out.

2.3. Ransomware Variations

As to the variations or types of ransomware, different cybersecurity companies and organisations identify different categories. The most commonly listed types are Crypto ransomware, Locker ransomware, Scareware, Doxware, RaaS and Double and Triple Extortion. Crypto and Locker ransomware were the original types, while the rest were developed in more recent years.

Crypto ransomware

is a highly prevalent and damaging form of malware that targets individuals and businesses by encrypting their files, rendering them inaccessible. It is often distributed through malicious emails, compromised websites, or by exploiting software vulnerabilities. Upon infection, the ransomware displays a prominent ransom note, demanding payment in cryptocurrency in exchange for a decryption key. This type of malware can encrypt all or a portion of the victim's data, while also employing shock tactics and fear to coerce victims into paying the ransom. It is important to note, however, that crypto ransomware often only encrypts the user’s data, and does not interfere with computer functions in general.

Locker ransomware

is a type of malware that blocks essential computer functions, denying access to the desktop and partially disabling the mouse and keyboard. This prevents normal operation of the computer, except for the ability to interact with a window containing the ransom demand for payment. The primary objective of Locker ransomware is to lock users out of their system, rather than causing complete destruction of data. It may employ social engineering techniques and compromised credentials to gain access to the system, displaying a pop-up on the victim's screen with false claims such as illegal website visits or virus infections. Once infiltrated, the malware presents a lock screen with a ransom demand, often accompanied by a countdown clock to create a sense of urgency and prompt victims to comply.

Double extortion ransomware

is a malicious software that encrypts files and extracts data in order to extort victims for a ransom. By utilizing this method, attackers hold the stolen data hostage and threaten to publicly release it unless their demands are met. Consequently, victims may find themselves vulnerable even if they are able to recover their data from backup. This is because after the 2017 NotPetya global phenomena, the luring nature of cyberattacks and the importance of backups became obvious to the world, which resulted in a lot of companies securing their data on external drives. Therefore, malicious actors needed an additional factor; not only do they make users unable to access their files, but the actors also threaten further steps. Most of the time this is to release the stolen data to the public, which could compromise the business on multiple levels: Intellectual Property could be leaked, providing undue advantage for competitors, employees could take legal action for their leaked personal information, and more. Although this type of double extortion – when the threat is to leak the data – is the most common, it is not the requirement for an attack to constitute double extortion. The threat could be a DDoS attack as well. It is important to note that complying with the ransom demand does not guarantee the security of the compromised data, since the attackers still retain access to the stolen information.

Doxware

also known as doxing ransomware or leakware, is a type of double extortion. It threatens to expose sensitive or personal information unless a ransom is paid. Unlike traditional ransomware that focuses solely on encrypting files, doxware takes a more intrusive approach by exfiltrating sensitive data and using it as leverage for extortion. Doxware typically gains access to systems through phishing emails, exploit kits, or compromised websites. Once inside, it not only encrypts files but also extracts sensitive data from the infected device or network. This can include personal documents, financial records, login credentials, or any other information that can potentially harm the victim's reputation or privacy if disclosed publicly. After exfiltrating the data, the attackers send a ransom demand. In some cases, the attackers may even release a small portion of the stolen data as proof to intimidate the victim into compliance. The emergence of doxware highlights the increasing sophistication of ransomware attacks and the shifting focus towards data exfiltration and privacy violation. The resourcefulness of ransomware groups is exemplified by their continuously evolving toolkits. In late 2020 a new technique, Triple Extortion emerged. The first case involved the Vastaamo clinic in Finland, where patient data was stolen and a ransomware attack was launched. The unique aspect was that the attackers not only demanded a ransom from the healthcare provider but also sent individual ransom demands to patients, threatening to publish their therapy session notes. In another instance, the REvil ransomware group introduced two additional stages to their double extortion scheme: DDoS attacks and phone calls to the victim's business partners and the media. These tactics aim to increase pressure on companies to meet ransom demands.[48]

Ransomware as a Service (RaaS)

involves a partnership between ransomware operators, who develop and maintain the ransomware software, and affiliates, who pay to use the ransomware to launch attacks. The concept of RaaS is akin to the Software as a Service (SaaS) model seen in legitimate software businesses. In RaaS, the ransomware operators create sophisticated ransomware strains and host them on dark web sites. They offer these strains as a subscription-based service, where criminals can purchase access to the ransomware for a fee. The pricing structure usually includes an entry fee to become a member and additional fees based on the complexity and features of the ransomware. The RaaS kits provided by the operators make it easier for affiliates to quickly launch ransomware attacks, even if they lack the technical skills or time to develop their own ransomware variants. These kits can be found on the dark web and are advertised in a similar manner to legitimate software products, complete with features like 24/7 support, bundled offers, user reviews, and forums. There are different revenue models employed by RaaS operators. Once an affiliate joins a RaaS program, they gain access to a portal where they can monitor the status of their infections, track ransom payments, and obtain other information about their targets. Some RaaS operators go to great lengths to create professional-looking websites, videos, and marketing campaigns, mimicking legitimate companies to attract affiliates. The RaaS market is highly competitive, and operators continually improve their ransomware variants to stay ahead. Affiliates play a crucial role in the spread and success of ransomware attacks, with the potential to earn significant profits. The average ransom demand has been increasing, and affiliates can earn up to 80% of each ransom payment, making RaaS a lucrative endeavour.

3. History of Ransomware

3.1 Timeline

The Early Days

The very first ransomware attack is considered to be the 1989 AIDS Trojan. This was distributed to 20.000 users on floppy discs at an AIDS conference. The virus would encrypt the users’ files and display a message instructing the user to mail the 189 USD “software licence fee” to a PO-box in Panama, in return for the “renewal of the software package”.[49] Looking back to this event more than three decades later, it does seem archaic; distribution through hard copies, mailing actual dollar bills. It is therefore not a surprise that ransomware did not become an immediate go-to method for criminals.

During the early days of the internet, a form of extortion became popular that did not even use encryption; scareware. It is a form of malware attack that preys on users' fears. Typically, scareware presents itself as fake security alerts or pop-up windows, claiming that the user's computer is infected with malware or experiencing critical issues, convincing them to take immediate action. The primary objective of scareware is to deceive users into paying a fee or purchasing fraudulent antivirus software. These fake solutions promise to resolve the non-existent problems or provide protection against the fabricated threats. It may utilize social engineering techniques, such as mimicking legitimate antivirus programs, using alarming visuals, and employing urgent language. The intention is to induce impulsive decisions from users, pushing them to buy worthless software, download additional malware, or visit malicious websites. While scareware can sometimes be a precursor to ransomware attacks, not all scareware directly causes significant harm. Some variants simply inundate users with persistent pop-up alerts without actually damaging their files.

The use of words and terms in Google often reflects the popularity or the coming into public consciousness of different concepts – although the popularity of using Google and the spread of smartphone usage needs to be taken into account as well. While in the early 2000s interest in ransomware was still relatively low, we can see an uptick in the figure below in around 2005. This is most likely because of the emergence of Archiveus trojan and GPcode. These ransomwares were using secure asymmetric encryption.[50] Although decryption was often possible even without a passcode – the Archiveus password was promptly cracked and released [51] -, the emergence of these technologies laid down the groundwork for future criminal activity.

Popularity of the term "ransomware" over time

2009-2013

Apart from the rudimentary nature of ransomware in the early 2000s, one other obstacle stood in the way of cybercriminals: payment. Bank transfers are easy to track down, and mailing bills takes time and effort. This is why the emergence of cryptocurrencies, particularly Bitcoin in 2010, was revolutionary in the ransomware domain. Cybercriminals could now demand payment through a nearly untraceable channel, ensuring their anonymity. From 2012, ransomware attacks became increasingly frequent.[52] However, one caveat which still prevented ransomware operations from becoming profitable businesses was that their victims often lacked the technical knowledge and skills to buy and transfer cryptocurrencies.

This time period saw the emergence of several ransomware tools, with the number of attacks increasing significantly. The following list contains the most important steps in ransomware development:

- Vundo (2009)

Vundo virus encrypted computers and sold decryptors, exploiting vulnerabilities in Java browser plugins or through malicious email attachments. It also attacked or suppressed antimalware programs like Windows Defender and Malwarebytes. - WinLock (2010)

The WinLock trojan, operated by a group in Moscow, locked victims' computers and displayed explicit content until they paid approximately $10. The group was eventually apprehended after amassing millions of dollars. - WinLock (2011)

The WinLock trojan was upgraded to pose as the Windows Product Activation system, tricking victims into reinstalling their software due to fraudulent use and extorting data from them. - Reveton (2012)

Reveton ransomware, categorized as scareware, impersonated US law enforcement and accused users of viewing illegal pornography. It displayed messages claiming legal consequences and demanded payment to avoid prosecution. Some versions even activated the user's camera to imply surveillance. - Mac Variant (2012)

A variant of Reveton ransomware specifically targeting Mac systems emerged. Although it was not cryptographic, it consisted of 150 identical iframes that appeared to lock the victim's browser. [53]

2013-2020

The next few years saw a continuous growth in both the number and the sophistication of ransomware attacks. First came CryptoLocker in 2013, which was the first ransomware to spread by botnet and due to its public and private 2048-bit RSA key encryption, it was particularly hard to decrypt.[54] Although its delivery mechanism, Gameover Zeus, was shut down by the FBI, researchers at CrowdStrike consider this event the “true inflection point for ransomware’s hockey-stick growth.”[55] Its successor, CryptoWall, spread by phishing emails and quickly became the most popular ransomware. It is estimated that by 2018 CryptoWall had caused 325 million USD in damages. In 2014 FileCoder and Oleg Pliss emerged, posing threat to MacOS for the first time, followed by KeRanger and Patcher in 2016 and 2017 respectively. In 2014, Spyeng was the first ransomware targeting Android, spreading through automatic messages from infected devices.[56]

2016 saw the emergence of RaaS, with Ransom32, shark and Stampado, but the world learned the real impact of ransomware in 2017. The infamous NotPetya attacks, attributed to Russian APT group Sandworm, destabilized thousands of entities worldwide, including governmental organisations, financial institutions, and more. The ransomware was spread through the EternalBlue vulnerability, and the final damage globally is estimated to be over 10 billion USD.[57] The same year WannaCry spread through the world as well, exploiting the same Windows vulnerability as NotPetya, causing up to 4 billion USD worth of damages. It is worth mentioning, however, that although NotPetya masqueraded itself as ransomware, no decryption key was ever provided, and therefore it is more accurate to describe it as wiperware.

The following two years were marked by the integration of GandCrab with information stealing malware, Vidar. This was the first time that information on the victims’ system could not only be locked but stolen as well, giving rise to the now dominant leakware, such as Maze. In 2019, leak sites were popping up, where the attackers would publish stolen data to pressure victims into paying the demanded amount. This additional manipulation technique proved useful – one group reportedly received over 25 million USD in 2020.[58]

The new age: from 2020 until today and beyond

Although the technology and sophistication of ransomware has not changed significantly during the last few years, our world has. A pandemic, a war, and global inflation opened the door for malicious actors to exploit new areas. This led to the continuous rise in ransomware actors – up until the second half of 2022. Most cybersecurity research reports that the third and fourth quarter of 2022 saw a noticeable decline in ransomware attacks. The cause is not obvious, but multiple theories exist. Some speculate that internal conflict in ransomware groups between Russians and Ukrainians led to the need for them to reorganise. An example for this is the breakdown of the Conti group which led to a significant impact on the ransomware market. Others theorize that businesses, organisations and governmental entities have finally upgraded their cybersecurity frameworks that attackers have a harder time finding vulnerabilities. Or maybe the growth in the number of attacks during the pandemic was simply an exception due to the global event, and the playing field is now getting even again. The most likely answer is that all these factors played a role in the decline of the number of attacks, as well as several additional events. It cannot be stated for certain, however, that the decrease will continue, and 2023 already saw an uptick. While new cybersecurity regulations are being adopted around the world regulating incident reporting, mandatory measures and more, threat actors may find new ways to achieve their goals. If they are facing obstacles today, they might have an even more effective and destructive solution tomorrow.[59]

3.2. Ransomware in Numbers

Number of Ransomware Attacks

Ransomware attacks have been steadily increasing throughout the years, but 2022 saw a decline in their numbers for the first time. According to Statista.com, the number of attacks worldwide decreased from 623 million to 493 million between 2021 and 2022, which is a more than 20% decline. This, however, reversed in 2023 with both March and September reaching record high numbers of ransomware attacks worldwide. The following figures demonstrate these trends.

Ransomware attacks over time

Source: Statista

There is already indication that 2024 will be continuing the trend of record breaking ransomware activity. For instance, the NCC Group reported that the number of attack in January 2024 superseded those in 2023. However, the direction of change indicates a downward trend; there has been 27% less recorded cases in January than a month before.[60] Therefore, instead of drawing overarching conclusions, the best approach is continuing awareness.

Number of Ransomware Actors

As discussed in Section 1, the number of ransomware actors cannot be precisely determined, but most researchers put their number between 100 and 200. Hunt & Hackett is currently monitoring 113 distinct ransomware actors, the majority of which are originating from Russia. However, this number does not entirely reflect the groups whose activity has come under the radar of our researchers, since most groups use affiliates for different stages of the attack. The question then arises whether these should be considered the same or separate actors, maybe tracked as different wings of the same few groups. This is how Ransomware-as-a-Service is developing.

The following threat actor groups are currently tracked by our researchers:

Agrius, ALPHV, ANTHROPOID SPIDER, APT19, APT21, APT27, APT29, APT3, APT31, APT32, APT33, APT34, APT35, APT36, APT37, APT38, APT40, APT41, Blacktail, BOSON SPIDER, BOSS SPIDER, BRONZE STARLIGHT, BuhTrap, CIRCUS SPIDER, Cobalt, CopyKittens, Daixin Team, Dalbit, DarkHydrus, DefrayX, DEV-0270, DEV-0569, DEV-0586, DOPPEL SPIDER, DragonOK, DUNGEON SPIDER, Earth Lusca, Evil Corp, EXOTIC LILY, FIN13, FIN6, FIN7, FIN8, Flying Kitten, Fox Kitten, FusionCore, GALLIUM, Gangnam Industrial Style, GOLD BURLAP, GOLD CABIN, GOLD DUPONT, GOLD GARDEN, GOLD MANSARD, GOLD NORTHFIELD, GOLD SOUTHFIELD, GOLD SYMPHONY, GOLD WATERFALL, GOLD WINTER, GRIM SPIDER, GURU SPIDER, HAFNIUM, Hellsing, Iron Group, Karakurt, LAPSUS, LockBit Gang, MALLARD SPIDER, MONTY SPIDER, MosesStaff, MuddyWater, MUMMY SPIDER, NB65, OldGremlin, OUTLAW SPIDER, OVERLORD SPIDER, PARINACOTA, PINCHY SPIDER, Prophet Spider, QUILTED TIGER, RIDDLE SPIDER, Sandworm, Scattered Spider, SCULLY SPIDER, Silence group, Silent Chollima, SilverFish, SLIME29, SMOKY SPIDER, STARDUST CHOLLIMA, Storm-0324, SunCrypt Gang, SWEED, TA2101, TA505, TA516, TA578, TA579, TeamXRat, TheDarkOverlord, The Gorgon Group, The Shadow Brokers, TianWu, Tick, Tortilla, TRAVELING SPIDER, UAC-0118, UNC1878, UNC2447, UNC2565, VIKING SPIDER, Void Rabisu, ZOMBIE SPIDER

Share of Attacks per Sector & Region

The overall breakdown of attacks per sector is difficult to determine, as different research companies come to different conclusions, often depending on the researcher’s expertise and the company’s client base. For instance, IBM reported that the most, 30% of attacks were in the manufacturing sector in 2022, while BlackFog’s data suggests the Education sector was mostly targeted with 29% of all attacks.[61] Unit42’s data indicates the majority of attacks taking place in the financial sector, ENISA’s report suggests the industrial sector, while Coveware’s research shows Professional Services to be the most popular target. Regardless, there are some common themes between the different findings. Financial and investment services, manufacturing industries, companies in the energy sector, the logistics sector, and retail consistently score high in these reports. Statista’s reporting also puts construction and hospitals on the top of the list.

When it comes to geographical location, the exact break-down of affected countries also differ, primarily within Europe. However, most research findings seem to align in that the most affected regions are North-America and Europe. Based on the attacks in 2023, Dragos suggests that 44% of all ransomware attacks took place in North-America and 32% in Europe,[62] while the NCC Group puts those numbers at 59% and 26% respectively.[63]

Damage and Costs

In the US it is estimated that roughly 200.000 USD is the average ransomware amount paid, but ransomware costs usually depend on a multitude of factors. In general, the bigger the company the smaller percentage of their annual revenue is demanded. On average, this is 2.8%. How much of the payment is covered depends on the type of insurance a company has. For instance, according to Check Point a CryptoLocker attack on an unnamed financial institution in 2021 resulted in 40M USD loss in damages, and another 60M USD in additional costs. In their case, insurance covered the whole amount of 100M USD. On the other hand, in 2017 a software company suffered 68M USD costs in loss of income, they paid 24M USD for remediation and response, and faced additional 50M USD costs in other areas. Out of the total of 142M USD damages, their insurance only covered 30M.[64] This example also shows that the ransom itself is often not the only or even the biggest financial burden during a ransom attack. On average it only amounts for 15% of the total costs. Cybersecurity Ventures predicts that by 2031, annual ransomware payments globally will amount to 265 billion USD.[65]

More Fun Stats

- Ransomware takes up roughly 20% of all cybercrime [66]

- 90% of ransomware attacks fail [67]

- Phishing is the most common entry point [68]

- In 2020 the highest average ransom was paid in the manufacturing industry, exceeding 2mil USD [69]

- 46% of victims with encrypted data paid the ransom [70]

- Global damage from ransomware attacks was 57 times higher than in 2015 [71]

- In 2021 cyber insurance fees grew by 92% [72]

- 14% of victims recover all their data, 3% recover none [73]

- 90% of financial institutions experience at least one ransomware attack each year [74]

3.3 Examples of Ransomware Families?

As described in previous sections, ransomware comes in all shapes and forms, and all specific distributed malware falls into a specific family. Between 2016 and 2018 the number of new ransomware families exploded, with two to three hundred new families discovered each year. Since 2019, however, that number has drastically decreased, with only 26 new families discovered in 2022.[75] This could suggest that the existing ones are efficient enough for attackers, or potentially they have lost interest in development. Some of the most prominent families can be seen in the figure below.

.jpg?width=700&height=560&name=Def%20Guide%20to%20Ransomware%20Charts%20(Photo%20Collage).jpg)

Source of the data:: Bitdefender

Going into detail about even just the most prominent ransomware families would go beyond the scope of this pillar page, which is why the following section includes a glimpse into only two of the most notorious examples of ransomware families.

GrandCrab

GandCrab emerged in January 2018 as a RaaS model. It quickly gained notoriety and became one of the most prevalent and impactful ransomware strains. It operated through a combination of social engineering techniques, exploit kits, and malicious email. One of the primary infection methods employed by GandCrab was malware-laden email attachments disguised as unpaid invoices. The ransomware also made use of exploit kits; Malwarebytes Labs reported the use of RIG, GrandSoft, Vidar, and Magnitude. It exploited vulnerabilities in popular software frameworks such as Struts, JBoss, Weblogic, and Apache Tomcat. GandCrab constantly evolved and adapted to evade detection and mitigation efforts by security firms. Its creators released multiple versions of the ransomware, incorporating new encryption technology and bug fixes. In response to the release of a free decryption tool by cybersecurity company Bitdefender, the GandCrab authors developed a new version that rendered the existing decryption tool ineffective.[76] The impact of GandCrab was severe, affecting both individuals and businesses worldwide. GandCrab utilized the ".bit" top-level domain (TLD). This allowed it to propagate through networks and infect a large number of systems, maximizing its potential impact.[77] Additionally, GandCrab affiliates utilized remote desktop protocol (RDP) attacks, attempting to gain unauthorized access to systems by guessing login credentials through brute force or dictionary attacks. The success of GandCrab can be attributed to its extensive affiliate network, diverse attack methodologies, and regular updates to its code. Its activities reportedly generated billions of dollars in illicit revenue for the operators, as mentioned in a farewell post on a cybercrime forum. Kaspersky Lab estimated that GandCrab accounted for up to half of the global ransomware market at its peak. After a 15-month reign of cybercriminal activity, GandCrab abruptly ceased its operations in May 2019.[78]

Raspberry Robin

Raspberry Robin, first identified in 2021, initially emerged as a relatively inconspicuous threat that commonly spread through USB drives. It utilizes autoruns or social engineering tactics to prompt users to click the LNK file. Upon execution, the UserAssist registry key is updated, indicating program launch. The worm's LNK file points to cmd.exe, initiating the installation of a malicious payload from compromised QNAP NAS devices. Raspberry Robin spawns additional processes using system binaries as living-off-the-land binaries (LOLBins), injecting into system processes and connecting to command-and-control servers hosted on Tor nodes. It achieves persistence by adding itself to the RunOnce key in the user's registry hive, pointing to a randomly named binary with a non-standard file extension.[79] By the end of 2022, Microsoft was raising concerns about the worm triggering payload alerts on devices belonging to nearly 1,000 organizations within a 30 day period.[80] The malware has introduced a deceptive tactic to confuse researchers and avoid detection; it now deploys a fake payload when it detects that it is running within sandboxes or debugging tools, aiming to mislead analysts.[81]

It is worth noting that although ransomware families are most often developed for targeting Windows systems, it is becoming increasingly common for attackers to focus on Linux as well.

Sources

[2] Microsoft: Over 100 threat actors deploy ransomware in attacks (bleepingcomputer.com)

[3] ENISA Threat Landscape for Ransomware Attacks (1).pdf

[4] ENISA p.25.

[5] Conti Ransomware: The History Behind One of the World’s Most Aggressive RaaS Groups | Flashpoint

[6] Conti Ransomware Group - Check Point Software

[7] Conti ransomware shuts down operation, rebrands into smaller units (bleepingcomputer.com)

[8] Ransomware Gang Conti Has Re-Surfaced and Now Operates as Three Groups: TRM Labs (coindesk.com)

[10] ALPHV, BlackCat Gang - Threat Group Cards: A Threat Actor Encyclopedia (etda.or.th)

[11] Everything You Need To Know About BlackCat (AlphaV) (darkreading.com)

[12] The many lives of BlackCat ransomware | Microsoft Security Blog

[14] Resecurity | BlackCat (aka ALPHV) Ransomware is Increasing Stakes up to $2,5M in Demands

[15] Colombian energy supplier EPM hit by BlackCat ransomware attack (bleepingcomputer.com)

[16] BlackCat said they breached US Department of Defense contractor and went offline | Cybernews

[17] https://www.otorio.com/blog/5-cyber-attack-motives-your-industry-may-face/

[18] 2017 Verizon Data Breach Investigations Report

[20] Chinese hackers use ransomware as decoy for cyber espionage (bleepingcomputer.com)

[22] What is the motivation behind ransomware? | Foresite

[25] Cyber attack hits 200,000 in at least 150 countries: Europol | Reuters

[26] Almost all WannaCry victims were running Windows 7 - The Verge

[27] WannaCry: Are Your Security Tools Up to Date? | The National Law Review (natlawreview.com)

[28] How to Accidentally Stop a Global Cyber Attacks (malwaretech.com)

[29] The Confessions of Marcus Hutchins, the Hacker Who Saved the Internet | WIRED

[30] 💬3 - 10 of the Biggest Ransomware Attacks in History (getastra.com)

[31] "WannaCry" ransomware attack losses could reach $4 billion - CBS News

[33] Ransomware attack on Colonial Pipeline is work of criminal gang called DarkSide, AP says - CBS News

[34] Colonial may open key U.S. gasoline line by Saturday after fatal blast | Reuters

[35] CYBERSECURITY RESPONSE (colpipe.com)

[36] Media Statement: Colonial Pipeline System Disruption (colpipe.com)

[37] Colonial Pipeline: US recovers millions in cryptocurrency paid to ransomware hackers | CNN Politics

[38] Colonial Pipeline: US recovers millions in cryptocurrency paid to ransomware hackers | CNN Politics

[39] CYBERSECURITY RESPONSE (colpipe.com)

[40] The Attack on Colonial Pipeline: What We’ve Learned & What We’ve Done Over the Past Two Years | CISA

[41] Joint Cyber Defense Collaborative | CISA

[42] VNG_IBD_Factsheet_Lessons-Learned-1.pdf (informatiebeveiligingsdienst.nl)

[43] VNG_IBD_Factsheet_Lessons-Learned-1.pdf (informatiebeveiligingsdienst.nl)

[44] UM in the world - UM in the world - Maastricht University

[45] ADDENDUM UM 06-02-2020 ENGELS.indd (maastrichtuniversity.nl)

[46] Maastricht University wound up earning money from its ransom payment (bleepingcomputer.com)

[47] Maastricht University wound up earning money from its ransom payment (bleepingcomputer.com)

[48] The New Ransomware Threat: Triple Extortion - Check Point Blog

[49] The History and Evolution of Ransomware Attacks | Flashpoint

[50] The History and Evolution of Ransomware Attacks | Flashpoint

[51] The History and Evolution of Ransomware Attacks | Flashpoint

[52] A Brief History of Ransomware [Including Attacks] - CrowdStrike

[53] The History and Evolution of Ransomware Attacks | Flashpoint

[54] The History and Evolution of Ransomware Attacks | Flashpoint

[55] A Brief History of Ransomware [Including Attacks] - CrowdStrike

[56] The History and Evolution of Ransomware Attacks | Flashpoint

[57] The History and Evolution of Ransomware Attacks | Flashpoint

[58] The History and Evolution of Ransomware Attacks | Flashpoint

[59] The History and Evolution of Ransomware Attacks | Flashpoint

[60] Cyber Threat Intelligence Reports - (nccgroup.com)

[61] Cyber Rescue Alliance: Best Cyber Insights of 2023, p.6.

[62] Dragos-2023-Year-in-Review-Full-Report.pdf p.23.

[64] Ransom payment is roughly 15% of the total cost of ransomware attacks (bleepingcomputer.com)

[65] Global Ransomware Damage Costs Predicted To Exceed $265 Billion By 2031 (cybersecurityventures.com)

[66] The Latest Ransomware Statistics (updated June 2023) | AAG IT Support (aag-it.com)

[67] The Latest Ransomware Statistics (updated June 2023) | AAG IT Support (aag-it.com)

[68] The Latest Ransomware Statistics (updated June 2023) | AAG IT Support (aag-it.com)

[69] Ransomware attacks, payouts soared worldwide in 2021: report | Cybersecurity Dive

[70] The State of Ransomware 2022 – Sophos News

[71]Global Ransomware Damage Costs Predicted To Exceed $265 Billion By 2031 (cybersecurityventures.com)

[72]Global Ransomware Damage Costs Predicted To Exceed $265 Billion By 2031 (cybersecurityventures.com)

[73] Cyber Rescue Alliance: Best Cyber Insights of 2023 p.81.

[74] 86 Ransomware Statistics, Data, Trends, and Facts [updated 2022] (varonis.com)

[75] Number of new ransomware families 2022 | Statista

[76] Who’s Behind the GandCrab Ransomware? – Krebs on Security

[77] GandCrab ransomware and how to prevent it - Trend Micro

[78] GandCrab ransomware - Removal and prevention guide | Malwarebytes

[80] Raspberry Robin worm used as ransomware prelude (malwarebytes.com)

[81] Raspberry Robin worm drops fake malware to confuse researchers (bleepingcomputer.com)