- SERVICES

- THREATS

- Sector-based threat landscape

- Agriculture

- Energy

- Maritime

- Manufacturing

- Technology

- Logistics

- Governments

- Country threat profiles

- Russian Federation

- China

- Iran

- North Korea

- United States

- Israel

- Threat actor profiles

- Fancy Bear/APT28

- Cozy Bear/APT29

- OilRig/APT34

- Charming Kitten/APT35

- Lazarus/APT38

- Double Dragon/APT4

- Sandworm

- Seaturtle

- Silent Librarian

- RESOURCES

- ABOUT US

- CONTACT

Spear Phishing: How it works and why you should care

Phishing has been around since the dawn of the internet, and by now most of us are wary of opening suspicious emails or messages. How is it, then, that phishing attacks remain ever so popular and successful both in absolute and relative numbers? Haven’t we learned our lesson?

Although phishing is only one of the many techniques malicious actors can use, it is involved in the majority of cyberattacks; some estimations suggest that as much as 90% of all data breaches were due to an initial phishing email.[1] Detecting and safeguarding against phishing messages can, therefore, have a meaningful effect on security. In order to achieve this, it is crucial to understand the attackers’ motivation, how phishing works, and what its consequences are. This understanding is essential for building an effective defence against such attacks.

Phishing in general has evolved significantly since that Nigerian prince first offered us his millions. Due to the broad umbrella of activities that may fall under the term, defining it is not an easy task. Most agree that in order for an attack to constitute phishing, there needs to be an element of social engineering delivered through electronic communication channels. It is not always obvious, however, if phishing should be restricted to online communication. “Vishing” or voice phishing, for instance, refers to the phenomena better known as scam calls, and these calls often take place entirely offline. On the other hand, “smishing” (SMS-phishing) operates much the same way as regular email-phishing, often relying on tricking the target to click on a link or to open a document containing malware, effectively opening the door for the attackers to infiltrate the targeted network. Discrepancies aside, the following definition provided in a 2013 IEEE paper[2] will help us understand the phenomena of phishing:

Targets & Motivations

One would assume that with the increasing societal awareness of malicious actors, and more and more sophisticated online security tools, the prevalence of phishing attacks would be decreasing. In fact, quite the opposite is happening. Our lives and businesses have been migrating into cyberspace for decades, and the COVID pandemic solidified this process with the explosion of remote work. In the meantime, technical developments, including new AI technologies, are providing more and more opportunities for malicious actors. The latest report[3] of the Anti-Phishing Working Group (APWG) observed a record high number of phishing attacks in 2022, with Business Email Compromise (BEC) and Advance fee fraud scams particularly on the rise. According to their findings, the most targeted sectors are financial institutions (23%), webmail providers (17%) and social media companies (11%). When examining how common phishing is compared to other types of cyber related criminal activities such as credit card fraud or tech support scams, a 2020 FBI report[4] concluded that “phishing/vishing/smishing” accounted for around 33% of all crime types. However, it is worth mentioning that the categories represented in this report do overlap in a significant manner. BEC, for instance, is handled as its own category, even though there is almost always a spear phishing element to it.

Phishing can take various different forms, the biggest difference being whether the attacker is truly waiting for any fish to bite victim to click, or the victim is predetermined and targeted. The latter is known as “spear phishing”, and it constitutes a more sophisticated version of the phenomenon. The targeted victim can be an individual, an organisation or a business. Attackers often personalize the phishing email to maximize its effectiveness, impersonating service providers the victim organisation is known to be using, or sending malicious attachment with news topics the receiver would be interested in. Although research has shown that young people under the age of 25 are statistically more likely to click on phishing links or attachments than other cohorts, and women are generally more likely than men,[5] there does not seem to be any indication that attackers target these demographic groups more. Anyone can become a victim of spear phishing, which is why constant awareness is crucial. For this, companies often launch security awareness campaigns, sending out “fake” phishing emails to see whether their workforce would fall for such tricks. It is important to keep in mind, however, that measuring change in employees’ behaviour is not easy, as the emails need to be similar in sophistication, but different enough for the user not to recognise the pattern. After all, attackers will most likely not follow the pattern.

But who are these attackers? Hacktivists in Guy Fawkes masks sitting in a dark basement? State-sponsored Advanced Persistent Threat (APT) groups from Russia or North-Korea? Your neighbour’s 15-year-old son? Any of these can be true. Phishing itself is merely a technique which could be utilised by anyone with malicious intent. What makes phishing attacks effective and dangerous is the coordination and resources behind them. This is particularly true for spear phishing, which often requires more time. For instance, a SoSafe report[6] revealed the extent of social engineering in a 2022 scam: after initial contact by the attackers pretending to be the victim’s acquaintance, they exchanged more than 270.000 words worth of messages before the eventual financial damage. To put this into perspective, that is more words than Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment, or Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix. In other words, in this spear phishing case there was a significant investment from the attackers to communicate and build trust with the target before the scam is executed.

Phishing, and specifically spear phishing can lead to a variety of different attack types, which often depends on the attackers’ motivation. Some attackers, such as ransomware groups, are financially motivated. According to a 2022 Kaspersky report,[7] spear phishing is one of the most common techniques used in ransomware attacks to gain initial access to the target network. The actors’ motivation is usually financial, although seemingly ransomware attacks have turned out to aim more for destruction, such as in the case of the infamous 2017 NotPetya attacks by Russian APT group Sandworm. Data destruction, as well as espionage and information theft are more common motivations for state-sponsored APT groups.

Although everybody can be targeted, there are certain sectors that tend to experience more attacks. The most targeted sectors include government agencies, technology companies, and increasingly banking and investment services. The latter has seen a shift change in recent years. Traditionally, financial institutions have been the main target of cyber-attacks due to their handling of large sums of money. However, they have become much harder to attack successfully do to their increasingly robust security operations. Therefore, threat actors are pivoting towards new opportunities such as in Venture Capital and Private Equity firms. Due to their nature, these companies often only employ a few dozen people, with access to huge sums of money. This makes them an especially attractive target. For instance, it has been reported that the 2021 “cybersecurity incident” against one of Silicon Valley’s oldest and most respected VC firms, Sequoia Capital, occurred due to an employee of the firm falling for a phishing attack.[8] The exact extent of the damage in this case is not known, but there is precedent of attackers hijacking millions of dollars from investment firms. This is in line with the knowledge and experience of Hunt & Hackett have gathered working with such firms.

Another way to distinguish phishing attacks is based on what exactly they are aiming to achieve with the specific emails. Credential phishing will call for different schemes than those used in phishing attacks for infection. Credential phishing, or more broadly phishing for information, is an attempt to trick users into offering their information. Fake login pages are a good example; victims receive an email about an unfulfilled payment for their Netflix account, and upon clicking on the link, they are asked to fill out their login details. The harvested data is then sold by the attackers or used in further operations. On the other hand, the aim of phishing for infection is to obtain code execution on an endpoint, usually a laptop. These kinds of schemes aim to infiltrate the entire network in order to, for instance, steal or destroy data. Opening malware infected documents attached to emails is an example for this.

The Origins of Phishing

Although it is rumoured that the possibility for a third party imitating a trusted service was discussed at a conference in as early as 1987, the first documented incidents of phishing took place in America Online (AOL) chatrooms in 1994, when a 16-year-old created the first ever automated phishing software AOHell, used for stealing account- and credit card information. The malware allowed the attackers to impersonate AOL customer service and requested sensitive information from the users. The first recorded use of the word “phishing” can be found in AOHell’s documentation.[9] However, the phenomenon didn’t reach public consciousness until 2001, when users of a payment system powered by digital gold currency were tricked out of their account information through cloned login websites.[10] As a response to the emerging phishing attacks in multiple sectors, the APWG was founded in 2003. Regardless, phishing campaigns arose on an ever-growing scale throughout the years, taking advantage of developing technologies. For instance, nowadays there is a variety of free and easily accessible grammar checking apps, and since the 2022 AI language model launches, the attackers do not even have to write their own phishing texts. Another change is that now it is not uncommon to see that instead of financial gains, cybercriminals aim to affect geopolitical situations.

APT (spear) phishing analysis

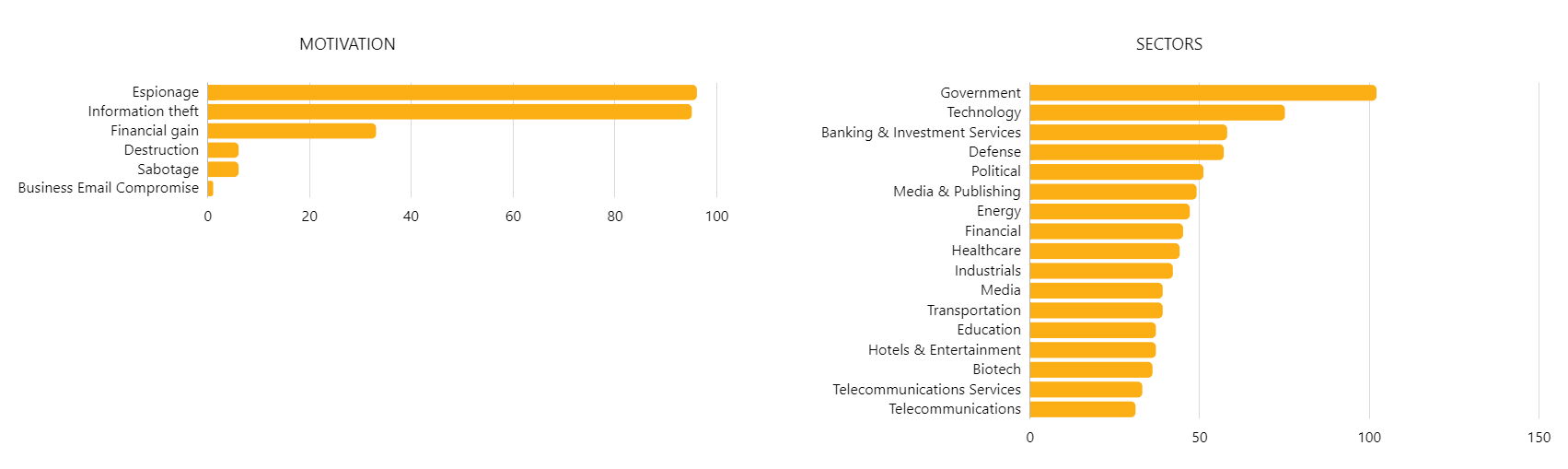

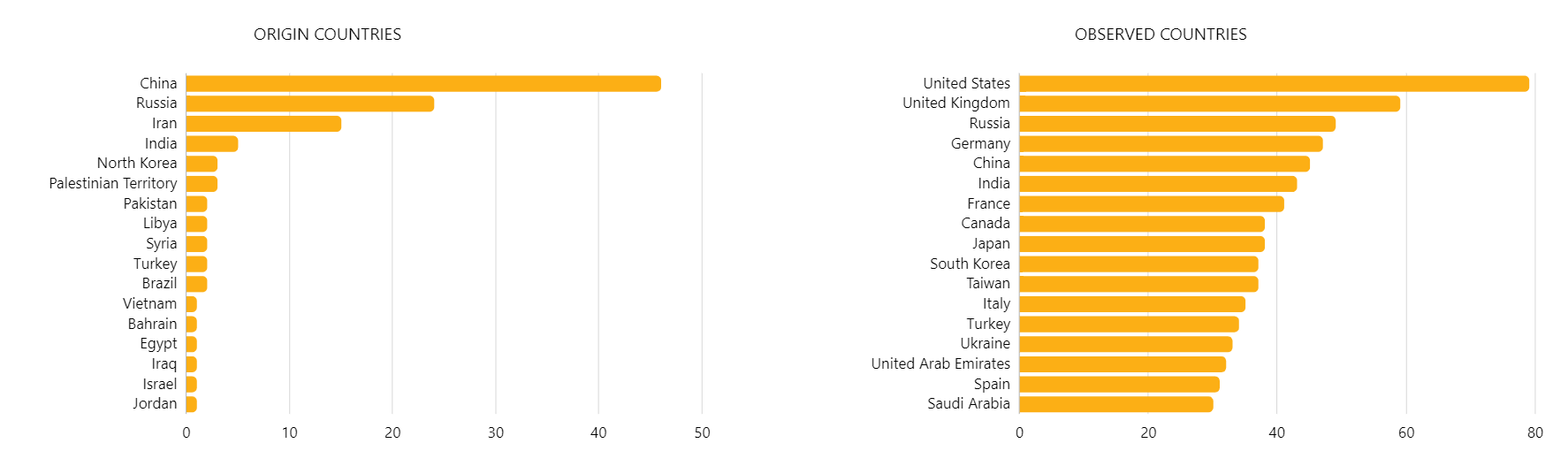

Hunt & Hackett is currently tracking more than 90 APT groups that are known to use spear phishing techniques in their attacks. These groups most often originate from China, Russia, Iran or North-Korea, and aim the majority of their attacks against the US, UK, Russia, India and China, although none of these lists are exhaustive. The motivation behind the phishing attacks varies widely from espionage, information theft or financial gain, to destruction and sabotage, always depending on the specific circumstances and the attacker. As to the sectors mostly targeted by phishing emails, it is worth emphasizing that any organisation in any sector can become a target. Based on the number of attacks, however, it seems that government organisations, technology companies, the defence industry and banking and investment services need to be particularly aware. Additionally, the healthcare and the biotech sector, media and telecommunication companies, the energy sector and the transportation industry have all suffered a large number of phishing attacks.

Most notorious APT groups heavily involved in phishing campaigns:

| North-Korea | APT38, Kimsuk y |

| Russia | APT29, Turla, Sandworm |

| China | T-APT-12, APT41, APT10 |

| Vietnam | APT32 |

| Iran | APT35, Chrysene, Muddy Water |

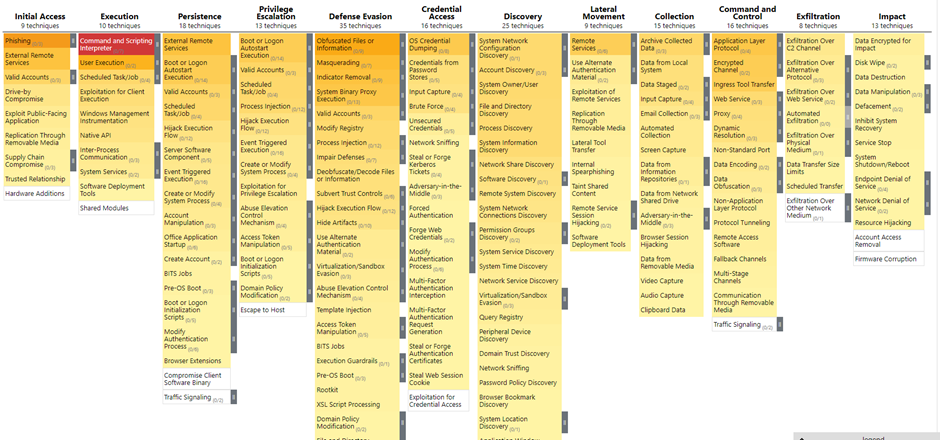

To understand how APT groups operate their phishing campaigns, it is important to examine what techniques they most often pair phishing with. In the early stage of reconnaissance, attackers often conduct Victim Identity Information Gathering (T1589). This can be done via open-source research, for example from the targeted individual’s social media profiles or the company’s website, or through a preliminary information gathering phishing campaign. The next technique, Command and Scripting Interpreter (T1059) at the execution phase of the attack is particularly important to keep in mind, as this technique is present at the vast majority of phishing attacks. Commands and scripts are usually embedded in the payload attached to the emails as documents or links. Connected to this is the technique of User Execution (T1204) similarly at the execution phase. This refers to the attackers deception of the users into execution the delivered malware.

At the later stage of defence evasion, there are two techniques that are particularly common in phishing attacks. Obfuscated Files or Information (T1027) and its 9 sub techniques is a method used to hide the executable or file, often by way of encrypting or encoding, compression or archiving. Masquerading (T1036), although not as popular of a defence evasion technique as the former, is also often used. This simply means that attackers manipulate the attachments so as to give the impression of a trusted source. This could include the file name, file type, metadata, or more.

Although dozens of techniques are commonly used in phishing campaigns throughout the attacks, the next phase with a particularly relevant connection to phishing is Command and Control. For this, Application Layer Protocol (T1071) and Ingress Tool Transfer (T1105) are most often used. The former is used to blend in with existing traffic in the network by embedding commands from the remote system in the protocol traffic, while the latter refers to transferring tools and files into the compromised system.

Insights into Spear Phishing Attacks by APTs

As mentioned earlier, the categorisation of different phishing techniques varies between security platforms and researchers. Knowledgebase MITRE ATT&CK classifies three subcategories for phishing; Spearphishing Attachment (T1566.001), Spearphishing Link (T1566.002) and Spearphishing via Service (T1566.003). In the following segment the following examples illustrating each type of spear phishing will be examined in order to understand how the attackers can infiltrate the victim’s system:

- A/ Attachments

- B/ Hyperlinks

- C/ Services

A/ Attachments

Spear phishing through email attachments have been used countless times. Most often these emails contain Microsoft Office documents or PDFs, with a cover story in the email persuading the target to open the document. Since deploying the malware this way relies heavily on User Execution (T1204), the text of the email usually emphasizes the urgency and importance of the message. The attackers often alter file extensions and icons in order to signal legitimacy. Once the victim opens the file containing malware, the payload either exploits a vulnerability on the victim’s computer, or directly executes on the system.[11] Hunt & Hackett has observed close to 70 different APT groups using this technique. Infamous Russian cyberespionage group known as APT28, or Fancy Bear repeatedly used spear phishing with malicious attachment. As an example, in 2018 APT28 sent out an email to employees of two different western governmental organizations. The sender’s email address (events@ihsmarkit@com) seemed to be legitimate, as JANES by IHSMarkit is a valid and trusted source of open-source defence information. However, later analysis proved that the address was spoofed. Impersonating a company operating in the national security and defence world was a particularly clever move, as this would not only lower the risk of detection in a governmental agency worker’s inbox, but it could also be incredibly attractive for them to read something in the topic. The attachment itself in this case was an Excel document titled “Upcoming Events February 2018.xls,” infected with the malware.[12]

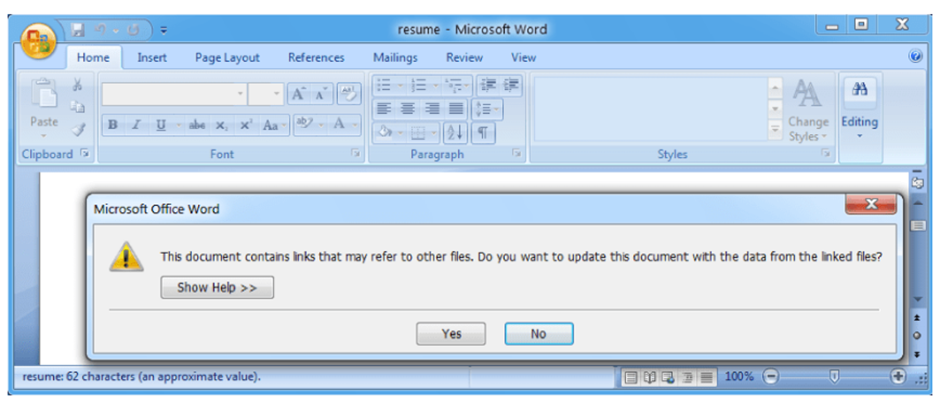

Another threat group observed to have made use of spear phishing emails through attachments is the Chinese state-sponsored espionage group, Leviathan. In a 2017 campaign they attempted to infiltrate the systems of two military related establishments: a shipbuilding company, and a university research center. Both of these are located in the US. One version of the emails, the one targeted at the university, landed in victims’ inbox with the subject line “Apply for internship position” and a document named “resume.rtf” was attached. Disregarding the logical fallacy that a sender would offer an internship position, as well as attach a resume, the scheme could have proven particularly effective had researchers not detected it in time. The tightening job market, especially in academia, would have played on students’ eagerness to secure work experience. Another spear phishing scheme, aimed at the shipbuilding company, used attachments named “ARLUAS_FieldLog_2017-08-21.doc” with the email subject line “Torpedo recovery experiment.” The social engineering aspect of this evidently relies on workers’ curiosity in their field. Upon opening, the file then exploited a then recently discovered Microsoft vulnerability (CVE-2017-8759).[13] The goal of these operations was most likely information gathering about the defence industry.

Source: Leviathan: Espionage actor spearphishes maritime and defense targets | Proofpoint US

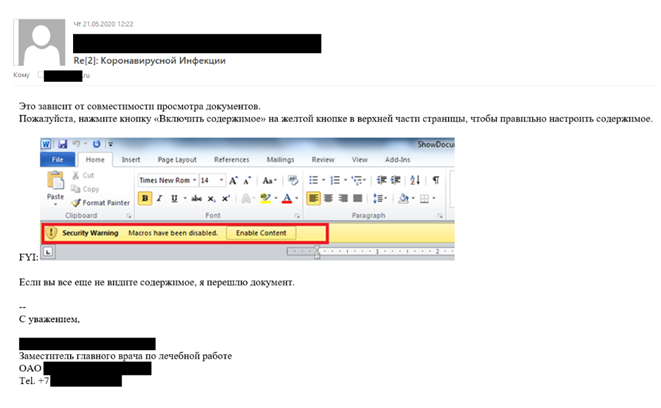

In 2020, the whole world shifted its focus on the global COVID pandemic, which was not lost on North-Korea’s most advanced APT group, Lazarus. Building on the fear surrounding the virus, the group sent out highly personalised and detailed spear phishing emails to users of the network of an unnamed Russian defence organisation. The attackers had conducted open- source research to gain information about both the targets and the alleged sender, which made it possible for them to include details such as names or positions. The emails seemed to have been sent from an address very similar to the organisation’s medical center, even though they were created with a public email service. The content of the attached Word documents was less well crafted, as they merely contained some general medical information rather than the specific urgent COVID-19 related news that the headline suggested. The attached document contained a macro which would then download and execute malware in order to infect the system. Although the first attempt in this specific scheme was unsuccessful due to macros in the system’s Microsoft Office being disabled, follow-up emails by the attackers explained the procedure of enabling them. This way, the system was eventually infiltrated. While it is relatively common knowledge that phishing emails can contain grammatical errors or spelling mistakes, the initial text, according to native Russian speakers, was meticulous. However, the language of follow-up emails explaining the procedure to enable macros in the documents was of considerably worse quality.[14]

Source: Lazarus targets defense industry with ThreatNeedle | Securelist

B/ Hyperlinks

The next popular spear phishing technique is the use of a hyperlink. Instead of an attachment containing the malware infecting the system, the victim would be tricked to click on a link embedded in the email. This is somewhat advanced compared to the use of attachments, since defence filters will not always flag suspicious links, only attachments. Currently there are almost 40 different ATP groups tracked within the MITRE framework who have been observed to use spear phishing via link.

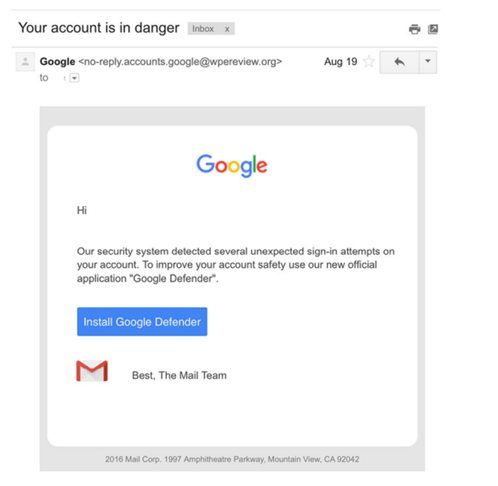

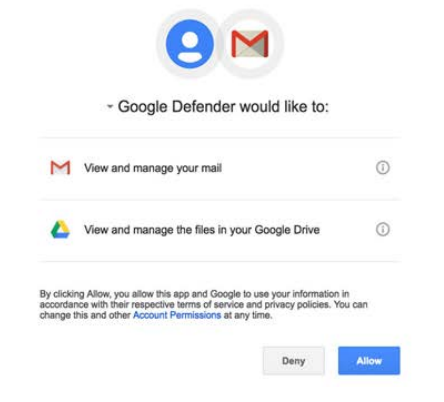

Spear phishing with a link often comes in the form of trusted email providers such as Gmail or Yahoo. Russian group APT28 conducted a large-scale credential phishing campaign in 2015 and 2016 targeting particularly high-profile users. This phenomenon, when the attackers focus exclusively on the highest-ranking users in a network such as CEOs or politicians, is often called whaling. APT28 used a simple but effective lure; they created email accounts which at first glance could be legitimate Google accounts (for instance no-reply.accounts.google@wpereview.org). The emails sent to the targeted victims encouraged the user to click on the “Install Google Defender” link in order to strengthen the account’s security. The link then led the victim to a legitimate-looking page where “Google Defender” is asking permission to access the user’s account. Once the victim allows this, the attackers have access to all user credentials. [15]

Source: Two Years of Pawn Storm Examining an Increasingly Relevant Threat (trendmicro.com)

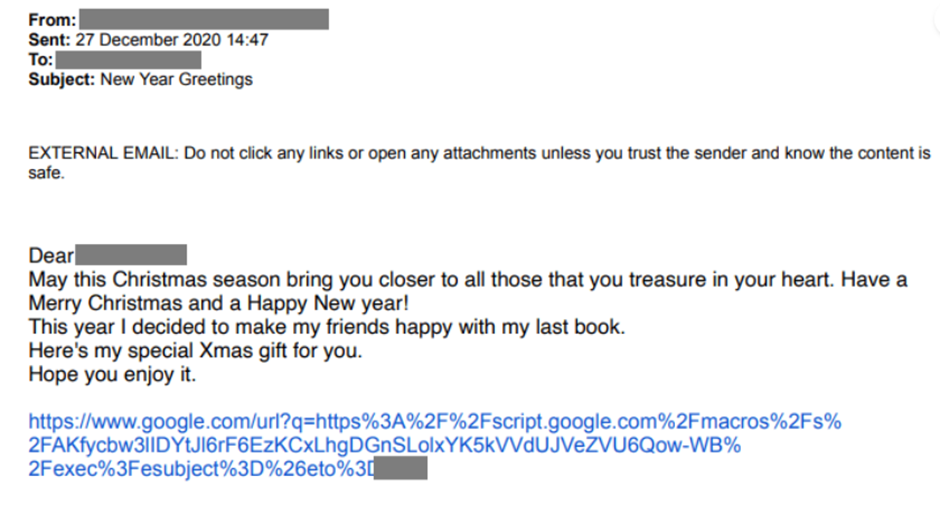

Another group known to use Spear Phishing with link is Iranian state-backed group, Charming Kitten. During the 2020 Christmas season the group carried out a targeted spear phishing campaign using previously hacked email addresses. This method can be more effective than fake provider addresses, since the target already knows the email address and presumably trusts the user behind it. Due to this connection, the emails sent out by Charming Kitten were often personal, using the holidays as a pretence. In this specific campaign, the attackers used redirection links in order to avoid email services’ security.[16]

Source: Charming Kitten’s Christmas Gift - Certfa Lab

C/ Services

Although email is the primary way of communication in business, attackers have been experimenting on other platforms as well. This resulted in an increasing share of phishing attacks carried out on social media platforms, such as Facebook, Twitter or LinkedIn. The latter can be particularly useful from the attackers’ perspective in the sense that potential victims voluntarily display the company or organisation they’re employed by, people are more willing to accept connection requests in order to broaden their network, and most people active on the website are at least somewhat involved in the job market. These factors make it more likely that attackers’ targets respond to connection requests and click on potential job ads sent to them by fake profiles.

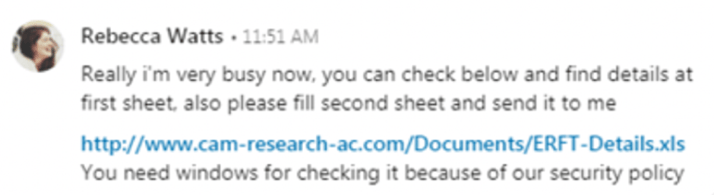

An APT group with Iranian connections often referred to as OilRig was identified behind a LinkedIn phishing campaign in 2019 by FireEye. The attackers created fake LinkedIn profiles pretending to be Cambridge University faculty members and messaged their targets in the energy, government, and oil and gas sectors with job offers. The messages included a link, clicking on which resulted in the downloading of malware such as TONEDEAF.[17]

Source: Hard Pass: Declining APT34’s Invite to Join Their Professional Network | Mandiant

Most people probably think that they would never fall for such phishing attacks. Decades on the internet have trained us to be aware of cheap tricks and avoid believing anything that sounds too good to be true. However, people with bad intentions are also evolving their techniques, and this can be particularly well done in the case of organised thread groups.

In 2021, a North-Korean state-sponsored group launched a campaign specifically against security researchers across multiple companies. Attackers created several Twitter profiles, a research blog and a YouTube channel. These different outlets were then used to amplify each other, providing a false sense of legitimacy. Twitter can be especially useful for this kind of targeted attacks, as contrarily to LinkedIn or Facebook, communication does not depend on an accepted connection request, and it is not suspicious to stay at least somewhat anonymous. Once a profile was convincing enough, attackers established communication with their targets, eventually proposing collaboration on vulnerability research. For this, they would send the victim a project created within Microsoft’s Visual Studio environment, which ultimately contained the source code for exploiting undiscovered vulnerabilities. Google’s Threat Analyst Group also discovered that the mere action of visiting the blog created and operated by the actors (based on stolen and copied material) through links on Twitter could result in becoming compromised.[18]

Recommendations and Conclusion

The examples in this article only represent a tiny portion of phishing campaigns carried out by malicious actors every day. As security researchers identify them and patch vulnerabilities, and the general public catches up with the latest phishing trends, there are already a number of new schemes on different platforms using different methods and tools. Regardless, it is important to stay alert and avoid falling for phishing campaigns. The following steps are by no means complete, but generally good practices to maintain your organisation’s security and help to make spear phishing attacks more difficult:

- Deploy phishing resistant multi-factor authentication methods to protect against credential phishing;

- Deploy anti-spam email filters and web-filters;

Configure these according to the most relevant threats. - Apply recommended security measures for the most used techniques;

Disable Office Macros or enforce signing. - Deploy initial allow-listing restrictions to prevent malicious file from being executed;

- Deploy modern EDR software and ensure it is being monitored and directly isolated when needed.

Lastly, if you wish to make use of awareness campaigns, these should be focused towards creating a safe space for employees to report suspicious activity. By now, we should have learned that employees are not necessarily the weakest link, they can be your strongest link in detecting security incidents.

Questions, concerns or feedback?

[1] https://www.tessian.com/blog/phishing-statistics-2020/

[2] *Khonji - Phishing Detection - 2013.pdf (romisatriawahono.net) p.2092.

[5] *pap1162-sheng (cranor.org)

[6] Cybercrime_Trends_23 - EN.pdf (sosafe.de)

[7] Common-TTPs-of-the-modern-ransomware_low-res.pdf (kaspersky.com)

[8] Silicon Valley VC Firm Sequoia Capital Told Investors It Was Hacked (businessinsider.com)

[9] Early Phishing (arxiv.org)

[10] Security History: The Evolution of Phishing (cisco.com)

[11] Phishing: Spearphishing Attachment, Sub-technique T1566.001 - Enterprise | MITRE ATT&CK®

[12] Sofacy Attacks Multiple Government Entities (paloaltonetworks.com)

[13] Leviathan: Espionage actor spearphishes maritime and defense targets | Proofpoint US

[14] Lazarus targets defense industry with ThreatNeedle | Securelist

[15] Two Years of Pawn Storm Examining an Increasingly Relevant Threat (trendmicro.com) p.21-22.

[16] Charming Kitten’s Christmas Gift - Certfa Lab

[17] Hard Pass: Declining APT34’s Invite to Join Their Professional Network | Mandiant

[18] New campaign targeting security researchers (blog.google)