- SERVICES

- THREATS

- Sector-based threat landscape

- Agriculture

- Energy

- Maritime

- Manufacturing

- Technology

- Logistics

- Governments

- Country threat profiles

- Russian Federation

- China

- Iran

- North Korea

- United States

- Israel

- Threat actor profiles

- Fancy Bear/APT28

- Cozy Bear/APT29

- OilRig/APT34

- Charming Kitten/APT35

- Lazarus/APT38

- Double Dragon/APT4

- Sandworm

- Seaturtle

- Silent Librarian

- RESOURCES

- ABOUT US

- CONTACT

Lights can go out: Espionage & disruption in the energy sector

The energy industry has been the target of an escalating number of state-sponsored cyberattacks. Hunt & Hackett has closely watched this trend and the ones behind these critical infrastructure attacks: Advanced Persistent Threat groups (APTs). To cope with this increasing threat, it is vital to understand who your adversary is, where their motivation lies and what is in their arsenal. This series of blogs will see to it that you find the answers you are looking for. It is investigated what motives lie behind the attacks and the identity of the most active attacking nations is revealed.

Table of Contents:

-

Introduction & Challenges

-

The Usual Suspects

-

The Netherlands as a Prime Target

-

Disruption in the Energy Industry

-

Sources

1. Introduction & Challenges

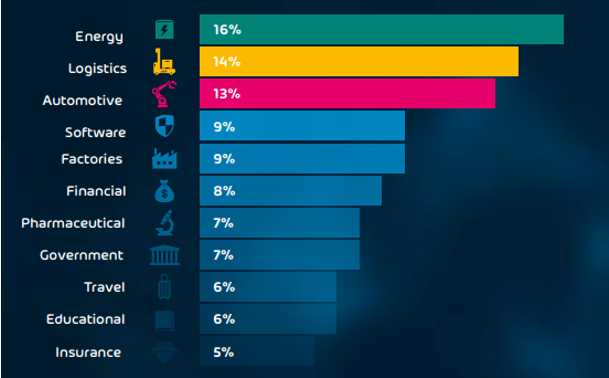

In 2019, the energy industry ranked as number one target for cyberattacks (and continued to be an increasing heavily targeted sector), with around 16% of all attacks occurring in this sector, as figure 1 shows1. To understand this apparent threat, it is crucial to know both the hunter and the prey. Examining both enables one to see and appreciate the value of the industry to adversaries. The reasons for adversaries to target the energy industry are even broader-ranged and more complex than for example the agriculture- or maritime industry. What’s different about the energy sector is that it’s interconnected with almost all other industries and even society as a whole. The energy sector literally fuels all industrial, IT and administrative processes. As a result, it plays a key role in many of the current geopolitical, economic and environmental issues, as well as military conflict situations. For adversaries, gaining access to a country’s energy grid or supply, which has a crippling effect on the ability to wage war or even run society as a whole, is like hitting the jackpot. It’s no surprise then that the energy sector is considered critical infrastructure.

Figure 1 – Most cyber-targeted industries in 2019 | Source: Hornet Security

So, what does the preyed upon sector in question look like? Overall, the Energy Industry encompasses three categories: (1) the exploration, production and refinery of energy as well as (2) the marketing, storage, distribution and transportation of energy and (3) the delivery of energy equipment and services2. Two forms of energy that flow through these categories can also be identified: non-renewable energy and renewable energy. Together, these forms of energy, fuel the world as we know it: trains, airplanes, cars, schools, hospitals, factories, offices, homes, etc.. As such, the energy industry is part of any nation’s critical infrastructure. As stated before, this is what makes this industry unlike others and why it has a deviating threat landscape as well. The subsequent cyberattacks that occur in the energy industry can generally be divided into different categories: (1) espionage and information theft, (2) disruption as a result of a financially motivated attack and (3) disruption as a (geopolitical or military) weapon, as is further outlined in the table below.

| Different types of motivations for cyber-attacks | ||

| Espionage and Information Theft | Disruption as a result of a financially motivated attack | Disruption as a weapon |

| Espionage and information theft are the motivations of actors who seek to enhance their present level of knowledge and acquire new technologies, trade secrets or other relevant business information for their benefactors. Governments influence or direct their APTs to infiltrate the IT-networks of its adversaries to extract business sensitive information or learn about the developments the target is making. In doing so, the instructing party can avoid lengthy R&D processes and/or gain an edge over its competition. All this while the attacking party faces a low risk of getting caught, due to difficulty of attribution and the remote nature of cyber-attacks. APTs often use the latest tools and tactics for these types of attacks. Espionage and information theft types of cyber-attacks are often quite sophisticated. | Disruption in cyber-security generally has one of two purposes. The most common purpose is financially motivated disruption. APT groups infiltrate computer systems of organizations and encrypt the data that is on it. The attacker threatens to publicize sensitive information or just block access to the systems necessary to run the business. These attacks are so called ransomware attacks. The sophistication level of disruptive attacks such as ransomware varies from generic and opportunistic to (advanced) targeted attacks. The recovery from such attacks is often complicated and time consuming as the encryption applied by the attackers is generally difficult to circumvent, leaving organizations to rely on their backup systems (which are typically compromised as well). In an upcoming blog, Hunt & Hackett will dive deeper into the world of disruption. |

The second purpose of disruption is about (temporary) disablement, malfunction and destruction to seize a tactical advantage. This means that through the deployment of malicious software, computer systems are (temporarily) limited from fully functioning or destroyed entirely. Information is manipulated, destroyed or made inaccessible. For nation-states, this could be a very powerful weapon to divert attention from or support (military) operations. In cases of political tensions or all-out war, entire countries can be put on the back foot or taken out through the disablement of their critical infrastructure. The power grid, dams, transportations, whole countries could be (temporarily) ‘shut-off’. Various APTs are believed to play the long game by gaining access and creating lasting persistence in critical infrastructure organizations of targeted nations to act as an insurance policy enabling the offensive nation to put pressure on targeted nation(s) when in need. |

| Examples | ||

| Compromised Norwegians | The Colonial Pipeline Hack | Ukraine Power Grid Hack |

Table 1 - The different types of motivations for cyber-attacks.

But what makes the energy industry a prime target for threat actors? Why do we see so many cyber-attacks with motives as they are featured in table 1? To fully understand the threat, it is of the utmost importance to know you adversary and yourself. As the legendary general Sun Tzu once famously stated: “if you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the outcome of a hundred battles.” This is why Hunt & Hackett doesn’t just examine the threats to the energy industry, but also drafts up a profile of the ongoing trends in the sector. By spotting the trends, one can determine what the strategic focus of adversarial APTs looks like. The three most important trends Hunt & Hackett has spotted in the energy industry are as follows:

- The ongoing energy transition;

- Digitalization of the industry;

- Decentralizing energy supplies.

Energy transition

Today, the energy industry is responsible for around 60% of the global greenhouse gas emissions. To cut down this enormous contribution to global warming, the industry needs to undergo a drastic transformation. The ongoing metamorphosis means transitioning away from fossil-based energy production systems, fueled by oil, natural gas and coal, and towards renewable energy sources. These include wind, solar and hydropower, but hydrogen and nuclear energy can’t be left out of the equation. The latter two, will be covered later in this blog (nuclear), and later in this series (hydrogen).

The transition in progress requires the optimalization of existing techniques, but even more the invention of new technologies. Some methods, like solar and wind power, are easily scalable. However, the problem here is that there is not yet a viable way to store energy derived from these methods in peak-moments for use in off-peak moments. Particularly for seasonal changes, as in the summer, solar power peaks, but its not possible (yet) to store this energy all the way through winter, when energy is most needed. Only through lengthy Research & Development projects, companies can try to create new ways to produce and store renewable energy through the seasons. On top of that, these R&D projects require unprecedented levels of investment. Market incumbents are not too eager to invest in new long-term projects to develop technologies when it is unclear how successful the outcome is going to be, which is often the situation. To do such research requires world class (technical) universities and research centers while the application, innovation and commercialization of such knowledge, Intellectual Property (IP) and technologies requires well-established start- and scale-up innovation and funding ecosystems that few countries have.

Governments recognize these problems and are looking for ways to effectively solve or bypass them. The renewable energy sector is being developed as a new frontier by universities, researchers, visionaries, innovator and (venture capital) investors that operate in parallel to the traditional (non-renewable) energy market. As innovation strives and the renewable energy market is maturing, governments are starting to see the benefits, as well as the effect it has on the economic and geopolitical landscape. Other governments do not have the patience, capital, infrastructure or will to invest heavily in renewable energy R&D projects, but prefer a quicker and cheaper way: by obtaining it directly from other nations.

In many countries, the mandate of intelligence agencies reaches beyond politics or national security. Most agencies are tasked with the safeguarding and enhancing the economic well being of the state, which means they actively hunt for trade secrets and intellectual property (IP) created by others in order to complement and enhance the existing knowledge and capabilities of their nation. The most efficient way to get this done, is by deploying cyber-force, or Advanced Persistent Threat groups (APTs). APTs have great advantages such as operating safely from a distance, low risk of getting caught, few consequences if they are being caught and being very cost effective. The cost efficiency lies in the fact that building cyber-capabilities requires investments in capabilities that can be easily deployed over a wide variety of operations while alternatives typically require heavy investment into single operations. This renders offensive cyberoperations highly scalable. If this wasn’t reason enough for nations to build offensive cyber-capabilities for economic gain, the risk of proper attribution is also very low and possible consequences are often mild. Hunt & Hackett has observed a sharp increase in the deployment of APTs in the energy industry over the last few years.

| Nuclear Energy |

|

There is no current discussion on the energy transition without mentioning the nuclear option. Many oppose nuclear energy for the danger it poses to the environment and the people living in its vicinity. Disastrous events like the meltdowns in Fukushima and Chernobyl have fueled opponents’ distrust gravely. Also, there is the ‘waste problem’. Nuclear waste’s radiation remains dangerous to life for thousands of years. Storing this waste is often regarded as saddling up future generations with today’s problems. Scientist are looking for ways to efficiently and safely store the nuclear waste or maybe even find a purpose for it. Another argument against nuclear energy is the tremendous cost of building powerplants. Proponents of nuclear energy however argue that nuclear power is the only way to safe the world from the devastating effects of the use of fossil fuels, before it is too late. Another major argument in favor of nuclear power over renewable resources is that the power generated is not dependent on seasonal circumstances, such as solar power. This takes away the problem of having plenty energy on peak-moments but needing the power off-peak. The US, France, China, Russia and South Korea are the biggest generators of nuclear power and have the most (innovation) knowledge and experience in this field. China has nearly doubled its generation capacity between 2016 and 2020 and has plans to build another 150 nuclear reactors4. Also, the UK is betting on a bright future for nuclear energy as well. Recently, the Brits announced a large investment in Small Modular Reactors (SMR) – smaller, cheaper nuclear plants. Other, less advanced countries like Iran and North Korea, who are emerging nuclear power countries, are seeking to upgrade their nuclear power capabilities. That these countries are not patiently awaiting legitimate R&D processes but are rather taking the illicit route can be derived from the fact that Teheran- or Pyongyang-sponsored APT-groups are often observed trying to infiltrate organizations that concern themselves with nuclear technology and knowledge. The latest example of this was the hack of a high-profile South Korean nuclear thinktank. The attack was attributed to Kimsuky, an APT that is likely an extension of the North Korean regime5. |

Table 2 - The nuclear energy landscape.

Digitalization

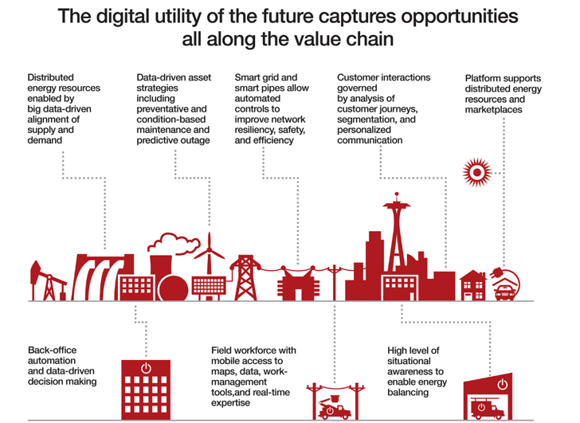

Another challenge the energy industry is currently facing, is digitalization, part of industry 4.0 (see figure 2). Increasing the use of the Internet of Things (IoT) offers new options to the production and management of available resources. At the same time, governments and regulatory institutions are attempting to push more accurate measuring systems and more efficient ways of generating and consuming energy, raising the pressure on companies. By doing so, governments hope to get a hold on the heavily polluting energy industries and to develop optimized policies based on its measured output, which promises to favor the whole economy. However, as an unintended consequence, the increased digitalization of the industry has given adversaries a much broader attack-surface, as well as access to systems that directly control the industrial side of the business. In a way this is ‘pure gold’ for APTs with disruption and sabotage missions. Hacker groups are always looking for ways in, digitalization gives them more doors to knock on. This means potential trouble for critical infrastructure, because it makes it much easier for attackers to establish an initial foothold in the computer systems of targeted organizations. Adding to that, the impact of potential breaches grows as well: when systems are interconnected, attackers have a much broader range of targets and can take over control of large parts of companies, reaching from production facilities to administrative and management departments. This is especially alarming news for organizations active in the energy- or related industries, because their critical value to society makes them a target for APT’s seeking disruptive leverage.

Figure 2 – Industry 4.0 in the energy industry.

Decentralization

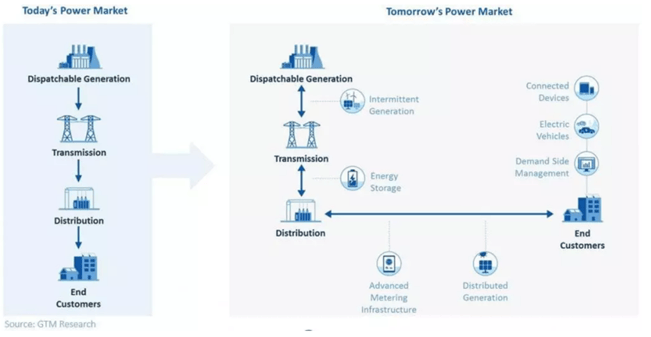

Traditionally, energy was distributed to consumers via large central power stations. Nowadays, this process is significantly more decentralized, with more producers in the field and consumers also being producers (so-called prosumers). Energy is flowing both ways, as is shown in figure 3 as well, for example via batteries, solar panels and small wind turbines. On the one hand, the decentralization of energy can contribute to a more sustainable energy economy because of the use of renewable energy sources and because energy can be stored in a much more efficient way. Efficiency increases because the generation of power is closer to the energy consumer, reducing the inefficiencies that occur during centralized transmission and distribution6. On the other hand, such a decentralized energy grid makes the systems significantly more complex and unpredictable, presenting a big challenge for countries that are trying to get a grip on their energy infrastructure. These decentralized grids are not (yet) capable of providing sufficient energy throughout the year, due to the lack of storage possibilities during peak-moments (summer), maintaining the need for a centralized grid too, which complicates the energy system even further. To make things worse, just as with digitalization, decentralization offers adversaries a much broader attack-surface, thus increasing the chance they will find weak spots to exploit. On the contrary, a decentralized grid in combination with (local) renewable energy sources have the future potential to enable countries to become less dependent on foreign energy sources, giving them a stronger geopolitical position. Today, however, this is still a distant future.

Figure 3 – An overview of today’s and tomorrow’s power market | Source: GTM Research.

In conclusion

For the energy sector, all types of motivations for cyber-attacks mentioned above are relevant. Companies invest heavily in finding solutions for the earlier explained challenges. The R&D projects meant to lead the way are nothing more but prey to APTs on the hunt for innovation, (trade) knowledge and (political) leverage. On the other hand, when a country has the power to disrupt another country’s energy infrastructure, the outcome of a hypothetical war is not hard to imagine.

When protecting the energy industry, the focus should be broader than just this industry itself. Connected industries, such as the technology and critical infrastructure industries, have great overlaps with companies active in the energy sector. The threat actors active in related industries are a risk to energy as well. Especially when looking at the long-term, APTs active in adjacent industries can easily hop over to energy.

Hunt & Hackett is aware of 255 APTs (of the ~430 known APTs to Hunt & Hackett in total), that have, now or in the past, successfully attacked the energy sector and related industries. Trying to find their way in, the APTs have deployed 2.087 Tactics, Techniques and Procedures (TTPs). This considerable number of APTs and their attacking methods show that nations are highly interested in attacking the energy sector. Hunt & Hackett applies an adversary central approach to defend its clients from cyberattacks, because only when you know both yourself and your adversary, you will be victorious.

| ATPs | TTPs | Tools | |

| Energy, Critical Infrastructure, Research and Technology | 255 | 2.087 | 1.980 |

| Energy and Critical Infrastructure | 122 | 1.476 | 1.451 |

| Energy | 118 | 1.419 | 1.406 |

Table 3 - The number of APTs, and the TTPs and Tools they used in energy and related industries as observed by Hunt & Hackett.

2. The Usual Suspects

China

China is the world’s largest energy consumer and its hunger for energy is ever growing. Mass-migration into big cities, rapid economic growth and a massive manufacturing industry have all contributed to the increase in the need for power. Currently, China relies greatly on coal as its energy source. The huge consumption of coal is the main reason for China’s position as the greatest contributor to global warming, emitting around one-quarter of all greenhouse gasses. The Chinese government has expressed the will to cut down these numbers and transferring away from coal to cleaner sources of energy. At the same time, China is by far the world’s leading country in renewable energy sources, such as wind and solar power, and has ambitious plans for nuclear energy. Besides from the beneficial long-term effects on the halting of global warming that come with the transfer from non-renewable to renewable sources, the Chinese population can also benefit on the short-term. The cities they live in are dealing with extreme air pollution; of the 100 most polluted cities worldwide, 48 are Chinese. Clean energy sources have the ability to improve quality of life and public health for the Chinese. To get to the point that China can call itself carbon-neutral, the Chinese government has formulated a plan in which science and new technologies have dominant roles7.

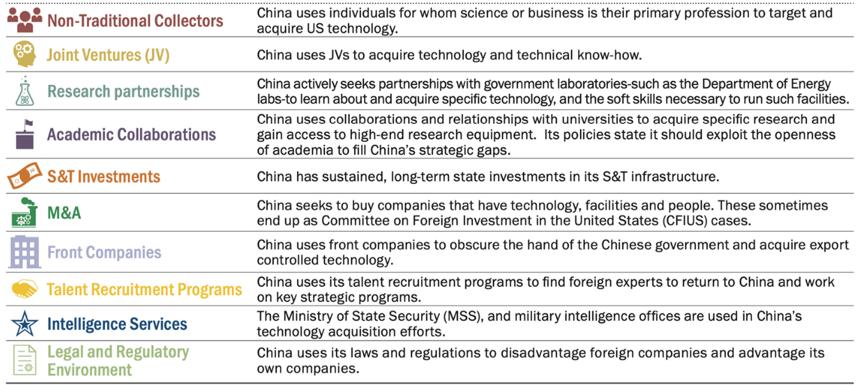

That is the part where China’s vast offensive cyber-capabilities come in. China has active policy in place to acquire western technology and intellectual property as part of the grand strategy Made in China 2025. China's cyberspace operations are part of a complex, multipronged technology development plan that uses licit and illicit methods to achieve its goals, as shown in figure 4. This strategy applies to the energy industry as well. The science and new technologies China needs to reach it long-term goals in the energy sector would take years of development and huge sums of money. If these can’t be achieved through licit ways such as academic collaborations, building start- and scaleup ecosystems, the merging of companies or joint ventures, why not use their highly skilled APTs instead? This saves loads of time and money while the chances of getting caught and facing consequences are low. In this way, China can get its hands on the most valuable and sensitive business information.

Figure 4 –China’s strategy on acquiring foreign technology and intellectual property | Source: Gerald Shastri, Reddit

.

Even though China’s main focus has been on espionage and information theft, recent reports have also outed suspicions of Chinese attacks on critical infrastructure with the goal of disruption8. Only last year, India fell victim to a cyber-attack on their power grid. There are signs that this was done by China, with whom India is in a border conflict, to send a threatening message to their enemy9. Incidents of disruptive cyber-attacks are more frequently outed by the victims or governments, partly because of their sometimes immediate impact on society. Information on incidents of cyber-espionage is less eagerly being communicated by the organizations that fell victim to them, wanting to protect their integrity. However, this doesn’t mean that there are less espionage attacks – they are just harder to find.

Hunt & Hackett outwits hostile APTs by tracking and anticipating their preferred attack methods (TTPs) and tools. Hunt & Hackett is aware of 69 APT-groups that have been linked to China and are currently or previously targeting energy or related businesses. It's worth noting that some of them are no longer operational or haven't been detected by other security providers in the last few years. Hunt & Hackett has identified 489 TTPs and 490 Tools used by these 69 Chinese APTs.

|

THREAT RECORD SHEET - CHINA - ENERGY INDUSTRY |

|

| "The Advancingly Powerful Threat" | ||

| Full Name | People's Republic of China | |

| Known Aliases (total of 69) | APT 10; APT40; APT41; Night Dragon; etc. | |

| Known Tools Used | 732 | |

| Known Methods Used | 524 | |

| EXCERPT OF PREVIOUS THREAT HISTORY | ||

| Date of Crime | Description Offence | Motivation |

| 2011-2013 | Chinese hackers infiltrated US critical energy infrastructure | Disruption |

| 2014-2020 | APT10 infiltrated critical energy infrastructure all over the world | Espionage / Information Theft |

| October 2020 | Chinese hacker group caused black-out by infiltrating Mumbai, India | Disruption |

Table 4 - Threat Record of China in the Global Energy and Related Industries.

Russia

Russia’s focus is quite different from China’s. Russia’s economy depends greatly on their fossil sources of energy. The Russian Federation is abundant with non-renewable energy sources. Oil, gas and petroleum products form the most important parts of exports with a share of over 60% of the upbringings of all exports. It’s estimated that over half of the world’s gas and close to half of the world’s coal can be found on and under Russian soil, and the Kremlin has not shown a lot of eagerness to steer away from using them. Russia’s great leader, Vladimir Putin, has spoken about the human impact on global warming in varying tones. One time Putin blamed ‘invisible changes in the galaxy’ for the occurring climate change, another time he stated that humanity is indeed a major contributor to global warming. Whatever he says, in his statements on global warming he has been reluctant to mention Russia’s fossil energy industry to this day. It’s important to note that Russia is the fourth largest greenhouse gas emitter in the world.

“changes of global character, cosmic changes, some invisible moves in the galaxy.”

-Vladimir Putin on what he thinks causes climate change, 201710.

It seems that Russia’s intentions with their energy industry mostly serve economic, geopolitical and military goals. There have been moments that the Russian government has acknowledged the impact humans have on the climate, but its actions have pointed at a completely different agenda. Russia’s vast fossil resources have given them a great geopolitical advantage over Europe and other neighbors. Without Russian energy, Europe is in serious trouble. It has happened multiple times before that Russia has played the energy trump card when in conflict with European nations. The European Union, when sanctioning Russian energy and financial industries in the aftermath of the 2014 Crimea invasion, have shied away from imposing sanctions on the gas industry, wisely bearing into mind that Russia provides around 40% of the EU’s gas supply11.

The motivations mentioned above do not directly relate to cyberattacks, how come Russia ends up second only to China in the most active attacking nations? This is for two reasons. First, Russia is heavily reliant on foreign technologies to modernize their (non-renewable) energy industry. However, due to international sanctions, they have a lot of trouble obtaining the required knowledge and technology for their modernization efforts. Deploying their highly skilled APT-groups helps Russia to get what they want in an illicit way. Second, Russia uses its APTs for the infiltration of critical infrastructure. They do this to assure that when in conflict, they have the ability to disrupt the energy supplies of their adversaries. This doesn’t just have a crippling effect on Russia’s potential enemies, but also deters them from even starting a serious conflict12.

Concluding, the cyber-threat Russia poses is multifaced and serious. Hunt & Hackett is aware of this threat and is currently tracking 27 Russian APTs, active in energy and related industries now or in the past, their preferred attacking methods (254) and the tools (1.086) they use (see table 5). This forms the basis of Hunt & Hackett’s data-driven approach to protecting its partners and safeguarding them from all cyber-threats.

|

THREAT RECORD SHEET - RUSSIA - ENERGY INDUSTRY |

|

| "The Sophisticated Destructor" | ||

| Full Name | Russian Federation | |

| Known Aliases (total of 27) | FSB; GRU; SVR | |

| Known Tools Used | 1086 | |

| Known Methods Used | 254 | |

| EXCERPT OF PREVIOUS THREAT HISTORY | ||

| Date of Crime | Description Offence | Motivation |

| 2016-2018 | Sophisticated attack by Russian government backed APTs on critical energy infrastructure | Disruption |

| 2020 | Russian hackers probing critcal energy infrastructure | Disruption |

| 2020 | Danish energy technology stolen and sold to Russia | Espionage / Information Theft |

Table 5 - Threat Record of Russia in the Global Energy and Related Industries.

Iran

The Islamic Republic of Iran can be considered an energy superpower. It has one of the biggest oil and gas reserves in the world. Within OPEC, it was the firth-largest oil producer in 2020 and third-largest gas producer in 2019. This enormous supply of resources could enable Iran to become a flourishing and wealthy country. However, there is a lot holding back the former regional hegemon. International sanctions, mismanagement of government and corruption in the bureaucratic system are major issues that prevent the Iranians from reaching their full potential.

Despite the growing global demand, Iran’s oil production has been in decline since 2017 due to underinvestment and severe international sanctions. Weighing heavy on the Iranian economy are the sanctions imposed due to Iran’s execution of its nuclear ambitions. The agreement reached in 2015, also known as the Nuclear Deal, between the permanent five members of the UNSC plus the EU put a halt to Iran’s efforts to obtain a nuclear arsenal. As a result, international sanctions were lifted, and Iran enjoyed the freedom of relatively free trade again. However, in 2018, President Trump of the US withdrew from the agreement and both sanctions and the nuclear program resumed.

Since then, Iran has experienced great difficulty with attracting foreign capital and technology. In the country’s Sixth Five-Year Economic, Cultural and Social Development Plan, it is stated that it wants to increase the share of renewables and clean power plants to a minimum 5% of its total capacity until the end of 2021. This indicates Iran’s willingness to transfer away from fossil fuels towards cleaner sources of energy. Their renewables industry is all but advanced, however, as the current level of clean energy used is estimated to be around 0,58% in 201813. Therefore, it is deemed unlikely that Iran has enough knowledge to make this transition on its own. More importantly, Iran is lacking the required financial capital to make serious progress in the energy transition. Iran needs foreign technology, capital and skills to become less reliant on the fossil industries. If they can’t get their hands on what they need through licit ways, due to sanctions, they will seek alternatives. Iran has the option of deploying a large group of APTs, recent history shows they are not reluctant to do so, who have the skills to infiltrate computer systems and steal intellectual property and other secrets.

The Iranian APTs are not seldom used to obtain information about nuclear arms or energy. Tehran is placing a lot of value in their nuclear program for both energy security and geopolitical power. Nuclear power forms the trump card of their position in international politics. With this in mind, it is no surprise that reports of cyberattacks attributed to Iranian APTs are often popping up. There are examples of attacks on Swedish high-tech nuclear organizations14 and British universities15 that were intended for the theft of intellectual property and other sensitive information dealing with nuclear technologies.

Next to stealing secrets, Iran also has shown interest in infiltrating the critical infrastructure of their enemies. In 2020, Iranian hackers attacked a water installation in Israel, seeking to disrupt their archenemy’s water supply. Israel claims that they were in time to detect and ward off the attack. This was the first publicly known attempt that Iran tried to disrupt critical infrastructure in the long-running Iran-Israel conflict16. Iran’s interest in disrupting critical infrastructure isn’t just limited to the Middle East. In 2013, Iranian hackers successfully tried to infiltrate a dam in New York, USA17.

A total of 25 Iranian APT-groups (now and in the past) that have been active in energy or related industries are known to Hunt & Hackett. To counter and to be prepared for their cyberattacks in the future, Hunt & Hackett tracks the TTPs and Tools they have employed in the past. At this moment, Hunt & Hackett has encountered 266 TTPs and 227 Tools used by Russian APTs in the relevant industries (see table 6).

|

THREAT RECORD SHEET - IRAN - ENERGY INDUSTRY |

|

| "The Middle Eastern Menace" | ||

| Full Name | Islamic Republic of Iran | |

| Known Aliases (total of 25) | APT 33; APT 35; Bahamut; BlackOasis; etc. | |

| Known Tools Used | 266 | |

| Known Methods Used | 227 | |

| EXCERPT OF PREVIOUS THREAT HISTORY | ||

| Date of Crime | Description Offence | Motivation |

| 2013 | A New York dam was hacked by Iranian threat actor | Disruption |

| September 2018 | Iranian hackers stole research on nuclear power | Espionage; Information Theft |

| April 2020 | Iranian hackers tried to increase chlorine to dangerous levels in Israeli water supply | Disruption |

Table 6 - Threat Record of Iran in the Global Energy and Related Industries.

North Korea

When the Soviet Union was dissolved in 1992, North Korea lost its most important trading partner, as well as access to subsidized oil from the communist giant. Since then, North Korea has struggled with meeting its energy demands and therefore suffers from chronic energy shortages. These shortages are primarily a result of the numerous sanctions that have been imposed on North Korea. The sanctions are the international response to North Korea’s prolific tests with nuclear weapons. The biggest part of the international community is trying to bind North Korean nuclear power by imposing sanctions severely limiting their ability to conduct trade. These sanctions restrict North Korea’s access to many types of energy. Still, the energy industry is of significant importance to North Korea, as coal exports are one of the main drivers of its economy.

As North Korea’s regime is centered around being self-reliant, it is looking for own ways to generate energy. It smartly uses its rivers to generate hydroelectric energy, but significant changes in weather conditions have resulted in a strongly decreased energy output. The call for finding new ways of generating energy were once emphasized in Kim Jong Un’s 2019 New Year’s address, in which he reportedly stated that he is looking for new ways to provide energy to his country, including tidal, wind and nuclear power. Although these are clean sources of energy, tackling global warming is not on the Supreme Leader’s agenda. He is a more concerned with North Korean self-sufficiency and solving the damaging energy shortages. For North Korea, it is all about energy security, also because a lot of their produced energy is absorbed by military activity. Therefore, it is not unlikely that Pyongyang is looking for ways to enhance their knowledge on renewables, also if that is not possible via the licit path…

Figure 6 – Satellite view of South and North Korea at night, illustrating the gap in development, infrastructure and the use of energy | Source: NASA Observatory

.

Well, the North Koreans must have nuclear energy, right? Despite North Korea having an estimated nuclear arsenal of 30 to 40 nukes, they don’t use nuclear power for energy generation. It is no surprise that a country that is so eager to establish energy security is looking for ways to use its nuclear capabilities for the benefit of their power supply. It is plausible, however, that they haven’t reached the required level of technology to do so. Acquiring the needed skills and knowledge would be a dealbreaker for the communist republic. As a result, there have been numerous reports of North Korean state-sponsored hackers targeting nuclear institutions for intelligence on nuclear technologies and other related IP.

There are reports that a North Korean hacker group, Lazarus, has hacked into nuclear and energy companies in several countries around the globe. Examples are Operation Sharpshooter and the attacks on an Indian nuclear power plant and the South Korean Atomic Energy Research Institute. Most of these attacks had the intention of stealing information on nuclear weapon technology, however, there are also reports of North Korean APTs targeting information that could benefit their nuclear energy industry. There also have been numerous accounts of North Korean hackers using ransomware or just stealing money from organizations all over the world for the purpose of scrambling up some money for their government, always in need of cash18.

Hunt & Hackett recognizes the North Korean cyber-threat to organizations working in the energy and related industries. In order to outsmart these digital adversaries, it is key to understand how they operate. Hunt & Hackett tracks their preferred attacking methods so you can build resilience against them. Hunt & Hackett has observed 7 APTs from North Korea targeting energy and related industries. In their effort, 133 TTPs and 221 Tools have been used, as is shown in table 7.

|

THREAT RECORD SHEET - NORTH KOREA - ENERGY INDUSTRY |

|

| "The Advancingly Powerful Threat" | ||

| Full Name | Democratic People's Republic of Korea | |

| Known Aliases (total of 7) |

Kimsuky; Wassonite; APT 37; APT 38 |

|

| Known Tools Used | 221 | |

| Known Methods Used | 133 | |

| EXCERPT OF PREVIOUS THREAT HISTORY | ||

| Date of Crime | Description Offence | Motivation |

| 2019 | Indian nuclear power plant infiltrated by hackers from North Korea | Espionage; Information |

| October 2018 | North Korean hackers target energy companies worldwide in Operation Sharpshooter | Espionage; Information Theft |

| 2021 | South Korean nuclear energy institute hacked by North Korean threat actor | Espionage; Information Theft |

Table 7 - Threat Record of North Korea in the Global Energy and Related Industries.

Below, in table 8, you can find a recap of the four most aggressive nation-states in the energy industry. The comparison shows their key objectives, their motives and other stats.

| China | Russia | Iran | North Korea | |

| Key strategic objectives |

|

|

|

|

| Level of cyber capabilities | Medium/ High | High | Medium | High |

| Known motives for cyber-deployment |

|

|

|

|

| Nature of risk to foreign ciritical infrastructure | Mostly Espionage19 | Disruption and Espionage20 | Disruption and Espionage21 | Disruption, Espionage and Financial22 |

| #APT groups | 69 | 27 | 25 | 7 |

| #TTPs | 524 | 254 | 266 | 133 |

| #Tools | 732 | 1.086 | 227 | 221 |

Table 8 – A comparison of the key objectives and statistics of China, Russia, Iran and North Korea.

3. The Netherlands as a prime target

The Netherlands, after the abandonment of the exploitation of gas fields in the north-eastern province Groningen, is no longer a major energy producing country. However, it does function as a hub to the global energy trade. Extensive networks of cross-border and subsea oil- and gas pipelines and electrical interconnections run beneath the famous fields of tulips. Next to that, Dutch ports (e.g. the Port of Rotterdam) also play an important role in the global energy trade. The Netherlands harbors close to 10.000 energy companies, of which a majority operates from the provinces Zuid-Holland, Noord-Holland and Noord-Brabant23. These components make that the Netherlands has an important role for the distribution of energy on the European continent. Moreover, the Netherlands is the cradle for many technological innovations, mostly due to the available human and financial capital, something the energy sector is yearning for.

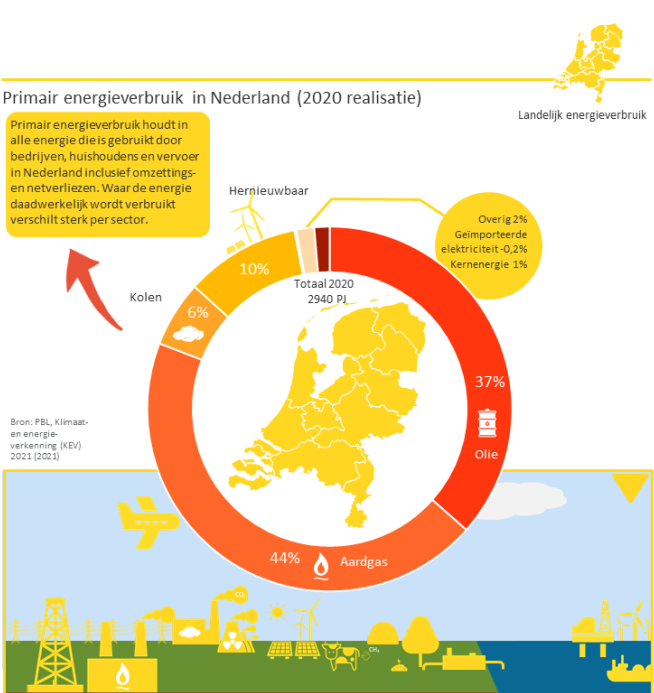

Even though the Netherlands is often regarded as an innovative and advanced nation-state, when it comes to renewable energy the Dutch are way behind other countries in the EU, such as France and Sweden, in transitioning their energy consumption towards renewable energy. The overwhelming majority of energy used in the Netherlands comes from oil and gas, as figure 7 shows. To catch up with this backlog, the government and energy industry have launched plans in which they state their green ambitions and how to get there. These plans have led to the investments of considerable amounts of budget in R&D, with specific attention to energy efficiency and renewable energy sources. Still, the Netherlands is largely relying on non-renewable energy, with several emission-intensive industries that are hard to decarbonize (e.g. agriculture, refining and chemicals production).

Figure 7 – Use of energy in the Netherlands in 2020 | Source: Topsector Energie.

Nevertheless, the R&D investments have led to fields in the renewable energy industry in which the Netherlands is a frontrunner. The government has drafted up a list of ‘key technologies’ for which they predict economic growth for the Netherlands. This list includes both non-energy technologies and energy-technologies. These are some energy related technologies that have made the list24:

- Energy Conversion;

- Energy Storage Materials;

- Power-to-Gas (hydrogen technology);

- Electrochemical Processes;

- Photovoltaics (solar cells).

The Netherlands is also a leader in electric vehicle (EV) deployment, EV charging infrastructure and is a front-runner in offshore and onshore wind energy technology. Such knowledge and technologies could be valuable to nation-states seeking to achieve their energy-transition goals. Protecting knowledge and technology that could help nations transition to more sustainable economies might feel a bit controversial, because why should companies keep their energy-transition tech for themselves if it could benefit the entire world? An answer to this question is that the incentive and financial benefits to create these technologies would disappear, just as the financial means to develop them in the first place. Therefore, it is vital that companies protect their trade-secrets and keep improving their technology and solutions.

Due to the Netherlands’ lack of sufficient (renewable) energy generation, they are highly dependent on foreign suppliers of energy. Most energy that is used in the Netherlands comes from Russia, followed from a distance by Norway. Turmoil between the Netherlands (or EU) and a major energy supplier - tensions with Russia for example are never far away - has the potential of major impact on the Dutch energy supply. A lighting example of this happened in de fall of 2021, when due to rising energy demand and less supply from Russia, Dutch energy prices soared. The Dutch dependence on Russian gas is nothing less than a serious geopolitical disadvantage. One of the ways to get out of this predicament is for the Dutchies to invest heavily in renewable sources of energy.

| The future politics of Hydrogen Fuel |

|

Earlier in this series of blogs, nuclear energy was discussed as a gamechanger for the energy industry, but a controversial one as well. Not everyone dares to double down on a future full of nuclear plants and radioactive waste. Lots of countries and companies are betting on another horse: hydrogen fuel. Hydrogen fuel is a gas, extracted from water in a process which requires energy as well. If this energy comes from renewables, it’s called green hydrogen fuel. The ideal production site for green hydrogen fuel is somewhere where there is plenty of space and access to renewable energy. A big plus is that hydrogen fuel can be easily stored and transported, in contrast to nuclear and clean energy. If hydrogen fuel becomes the next big thing, an enormous shift in geopolitics is upon us. Traditional purveyors of non-renewable energy, like Russia and Saudi Arabia, could lose their bargaining chip to countries that are leading in the hydrogen fuel industry25. The landscape of energy providers would be much more varied and possibly greatly different from the today’s image. Superpowers that derive their geopolitical strength from the fossil energy industry would have to surrender at least some of their influence. The diversified landscape of energy suppliers could be the solution to a problem many Western countries encounter when their energy supplier commits acts of human rights violations or other crimes. In the ideal case, countries would boycott suppliers that operate outside international law – a form of ‘energy democracy’. Time will tell if this ideal becomes reality. |

Table 9 - The future politics of Hydrogen Fuel.

Hunt & Hackett has observed a total of 18 APTs to have been active in the Netherlands’ energy industry. Most of these attacks were motivated by espionage and information theft, indicating that the Netherlands has caught the eye of malicious actors seeking to enhance their own energy industries. Left unprotected, Dutch advancements as a result of expensive R&D efforts could be undone by crafty APTs. The origins of APTs that already have been spotted attacking Dutch energy enterprises can be found, unsurprisingly, in China, Russia, North Korea and Iran, nations that were discussed earlier in this blog series. It’s only a matter of time before the Netherlands follows in Norway’s steps, which saw two of its major innovative energy companies attacked in the last two years, resulting in tens of millions of dollars worth of damage26.

The threat is closing in and is already hitting companies active in the Netherlands. Just days before the release of this blog, word got out that OilTanking, a massive tank logistics company from Germany, was hit by a serious cyber-attack, paralyzing much of its operations. As the story developed, it became clear that around 17 oil terminals, spread out over Europe, have been targeted in the attack. Six of the terminals are situated in the ARA-area (Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Antwerp). The impact of the attack and the motivations behind remain unknown27. Clear is that energy companies in the Netherlands should remain vigilant.

“Research from the Dutch intelligence agencies AIVD and MIVD shows that multiple Dutch top industries have been targeted for the purpose digital espionage. It mostly concerns the industries of high-tech, energy maritime and life sciences & health.”

-National Coordinator for Security and Counterterrorism (NCTV), CBSN 2020

Hunt & Hackett helps organizations in the energy industry to safeguard the products, technologies, and IP investments. Newly developed technologies and intellectual property that are related to the energy industry are high on the wishing-list of foreign adversaries. By tracking their every move, mapping their strategies and outsmarting their tactics, Hunt & Hackett assures that its partners are protected against any cyber-threat.

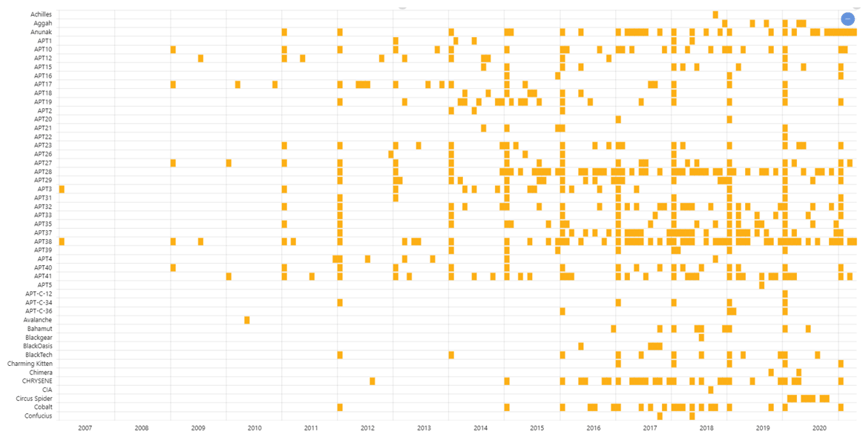

Figure 8 – Only a few of the APTs Hunt & Hackett tracks and when they have shown activity in energy or related industries globally.

As figure 8 shows, the threat to the energy- and related industries has drastically increased. Hunt & Hackett is highly vigilant and has the skills to counter this threat. We protect the digital environment of highly innovative companies and make sure that their secrets don’t fall into the hands of malicious adversaries. The approach we apply is data-driven and adversary-central: Threat Modelling.

4. Disruption in the energy industry

Nowadays, many companies dealing with critical infrastructure are transforming their IT-infrastructures to take advantage of the benefits of digitalization and in particular trends such as connected OT, IoT (smart everything), and decentralization. The speed of this transformation will only increase in the coming years. Although digitalizing critical infrastructures arguably provides many benefits, such as increased efficiency and reduced costs, it also creates a much larger attack surface for disruptive cyberattacks. Downtime of such critical infrastructure is already increasing, having potentially disruptive consequences on a societal level. What if nobody could make financial transactions anymore because all the payment systems are down? Or what if communication networks were down and you cannot call any emergency services? Or the power supply is disrupted for a prolonged period of time? Not coincidentally, critical infrastructures sit on top when it comes to the (potential) impact of disruptive cyberattacks and are therefore high-profile targets for a multitude of threat actors. Whether it is a politically motivated nation-state actor that uses disruptive cyberattacks as a mode of deterrence or retaliation, or whether it is a financially motivated threat actor that wants to create extra incentives to make its target pay ransom.

The energy industry is an essential part of the critical infrastructure and will be the focus of this blogpost. What makes the energy sector particularly vulnerable to such disruptive attacks? What could be the consequences of a disruptive attack in the energy industry? What role do geopolitics play? We will discuss this in the remaining part of this blogpost.

A target for cyber-attacks

There are two factors that make the energy industry particularly vulnerable to disruption: the large supply chain and increased IT-OT integrations. Operations in the energy industry are increasingly integrated for efficiency purposes. The downside of this integration is that it also creates greater interdependencies, therewith increasing the attack surface of the industry. In other words, disruption in one part of the supply chain can case a ripple effect on other parts of the chain. In May 2021 for example, American pipeline operator Colonial Pipeline became victim of a ransomware-attack. As a result, Colonial Pipeline decided to fully shut down operations in order to contain the threat. Although operations resumed a couple of days later, there were already gasoline shortages, with many empty filling stations and impacted flight schedules at multiple airports. This example illustrates how disruption in one pipeline operator can lead to far-reaching physical consequences in other parts of the energy supply-chain.

The energy industry has not always been a prime target for cyberattacks. Originally, the industry consisted mostly out of mechanical or analogue equipment, segregated from networks and the internet. OT systems are notorious for running outdated legacy software. Today, however, such systems are increasingly integrated with internal networks and even directly with the internet for its ease to fulfill remote maintenance tasks. At this point, many energy companies have started to use Industrial Control Systems (ICS), which are more publicly available and less expensive than proprietary systems. Although this sounds like – and probably was – a logical choice for many companies, the fact that these ICS solutions are coupled with IT-networks, and therefore have much more public facing, have led to more malware being available to target precisely these ICS. Moreover, OT systems were never designed to be connected to the internet, resulting in a disregard for any cybersecurity features. Especially Supervisory Control And Data Acquisition systems (SCADA) are an interesting target for disruptive attacks. In the energy industry, SCADA systems are used in oil and gas pipelines, but also in the electrical grid for transmission and distribution. If one would get access to such systems, operations could be disturbed or shut down, preventing the production or distribution of energy resources.

Hence, the energy industry is vulnerable to disruption. By attacking ICS, the production and distribution of energy can be compromised. Together with strong interdependencies in the supply chain, attacks on the energy industry can have far-reaching and physical consequences, whether being gas shortages, irreversible damage to production systems or even complete electricity outages.

Now knowing that the energy industry is vulnerable to disruption, the question arises: what do threat actors seek to achieve by launching disruptive cyber-attacks? For financially motivated actors, the disruptive impact of a ransomware attack on the energy industry makes sure that their victims are under the highest amount of pressure to pay the imposed ransom. For nation-states, however, the motivation lies in the geopolitical impact disruption could have, as is discussed below.

Geopolitical impact of disruption

At the end of World War two, the world was shocked by a weapon that had no equal. The obliterating power released by nuclear fission, a new technology, changed how the world looked at warfare forever. Cyberspace has offered a new weapon that is at the other end of the spectrum as it is stealthy and sly of nature but could have devastating consequences when used correctly. Through the use of offensive cyber-tactics on critical infrastructure, nations can completely blind and disable their adversaries. In the event of an imminent invasion or just as a warning, the cyber-threat is ever so real. The industry where the impact of such an attack would have the most impact, is the energy industry, as it quite literally provides the fuel for all other industries.

Nation-states with malicious intent are seeking for ways to infiltrate the critical infrastructure of their adversaries, building up a powerful leverage position if they ever came to need it. There have been examples of nation-states already exploiting the leverage position they built. In 2015, Russian hackers killed the lights in parts of Ukraine, and in 2018 in India, Chinese hackers, allegedly attacked the power grid of Mumbai. The first operation can be seen as another move in the ongoing Russian-Ukrainian conflict, the latter as one in the Chinese-Indian border conflict. Arguably, the most notorious example of all has come from the West. In June 2010, a computer worm called Stuxnet spread itself through the computer systems of a uranium enrichment plant in Iran. The level of sophistication of the worm was – and might still be – unprecedented. Stuxnet made the plant’s centrifuges spin out of control, while the data the control systems communicated back to the stunned nuclear scientist didn’t show anything out of the ordinary. The inflicted damage meant a set-back of years for the Iranian nuclear program. The highly advanced cyber-attack was never officially claimed, but the greatest suspicion rests on the US and Israel. These are not only countries that are among the strongest opposers of Iranian nuclear weapons, but they are also the only ones capable – then and arguably now – of engineering such an advanced cyber-attacks28.

These are only two examples of the use of cyber-disruption as an expansion of countries’ arsenals in modern warfare. Over the past years, concern over the state of defense of Western critical infrastructure, such as the energy industry, has grown. International relations between the world’s superpowers are tensing up and it is not unlikely that China, Russia and the US will flex their offensive cyber muscles. A contemporary conflict this trend is more than apparent in, can be found in Taiwan, which sovereignty is contested by its big brother, China. The small Eastern Island is already enduring a dazzling 20 to 40 million cyberattacks per month. These attacks mostly originate from mainland China and go way beyond just interfering with Taiwanese military activities – China is aiming to undermine their entire society29.

"The operation of our government highly relies on the internet. Our critical infrastructure, such as gas, water and electricity are highly digitized, so we can easily fall victim if our network security is not robust enough."

Chien Hung-wei, head of Taiwan's Department of Cyber Security.29

As explained earlier in this series of blogs, using APTs is increasingly popular among nation-states due to their easy scalability and low risk of attribution. What the Taiwanese, Indian and Ukrainian examples are clearly telling, is that cyberattacks are used as a method of pressure. Pressure to submit your adversaries to your will. It may also have become a tool of deterrence (arguably, see below), propaganda, and a weapon of warfare.

Cyber-attacks as means of deterrence

As briefly mentioned above, deterrence is a topic of discussion in the cyber-security community. With state-sponsored cyber-attacks daily occurring in high numbers, it is a relevant discussion, especially for those occupying themselves with critical infrastructure, such as all organization in the energy industry. The focus of the debate within the cyber(-scientific) community is on whether offensive cyber-capabilities can be and are regarded as means of deterrence. The deterrence theory became well known during the Cold War and describes how one party can convince another party to not take action by using threats or using relatively small amounts of force. A commonly known example of this is nuclear deterrence; it is highly unlikely for nation A to attack nation B if the latter has nukes that could inflict harm of an unimaginable magnitude on nation A. In other words, deterrence was mainly what kept the Cold War cold. Having the cyber-capabilities to paralyze an adversary’s energy infrastructure could deter the adversary from attacking. A successful cyber-attack on, for example, the power grid could have a massive impact. Does knowing that your target has the capabilities to launch such a devastating attack deter you from attacking? Can we state that deterrence is possible in the cyber-domain? Can nations or maybe even organizations refrain adversaries from conducting cyber-attacks directed at them?

“Thus far, the chief purpose of our military establishment has been to win wars. From now

on its chief purpose must be to avert them.”

Bernard Brodie, military strategist, illustrating the deterrence effect, 1946.30

Over the past years, many scholars from all over the world have been pondering these questions. As far as conclusions can be drawn on this subject in development, the answer for most scholars is: yes, but to a limited extent. The threat of retaliation is an important part of deterrence, but attribution of a cyber-attack is extremely hard, especially when it’s conducted by sophisticated nation-state actors. Adding to that, there is a great variety of actors in cyber-space, ranging from criminals to intelligence agencies, which means there are many motivations for cyber-attacks, making attribution even harder. Also, the red line, that is often more clear in other domains of warfare (sea, land, air, space), has not been drawn yet. Other scholars additionally argument that nation-states should regard cyber-space as one of the domains of deterrence, as in itself it’s just not enough31.

So, concluding on deterrence, current belief is that deterring adversaries from attacking you through cyber-space is very hard and only possible to a certain extent. Scholars are suggesting to provide another framework for cyber-space than deterrence, but on what this framework should look like there’s no consensus yet. Perhaps luring conflicts, such as Ukraine-Russia or China-Taiwan/India/US will show if cyber-deterrence is possible. As a consequence, it is most likely that the number of cyber-attacks and its use as an effective means for supply-chain disruption is likely here to stay.

Conclusion

In summary, the energy industry, as part of critical infrastructure, is extremely vulnerable to disruptive cyber-attacks. From the way the IT and OT systems are being set up to IT-networks and (indirectly) to the internet, to the major implications of disruption in this sector, the energy industry has a target painted on its back, due to its attractiveness to cause supply chain havoc. Financially motivated actors are drawn to the sector due to the frightening impact their ransomware attacks could have, while nation-states seek to find points of leverage to disable their adversary’s capabilities, or even deter them from engaging in conflict at all.

This blog on disruption concludes the Hunt & Hackett series on the cyber-threats occurring in the energy industry, globally and in the Netherlands. The current trends and challenges for the industry have been analyzed and compared to the strategic interests of the most aggressive nations in the cyber-space of the energy industry, as data by Hunt & Hackett had indicated. These adversarial nations, being China, Russia, Iran and North Korea, are driven by a variety of motives but are united in the fact that their cyber-aggression has only just begun. Organizations active in the energy industry should remain vigilant and anticipate incoming cyber-attacks.

5. Sources

- https://energymonitor.ai/tech/digitalisation/cybersecurity-threats-escalate-in-the-energy-sector

- https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/careers/jobs/energy-sector/

- https://www.iea.org/reports/power-systems-in-transition/cyber-resilience

- https://www.bloomberg.com/news/videos/2021-11-03/china-is-planning-at-least-150-new-nuclear-reactors-video

- https://www.zdnet.com/article/north-korean-hacking-group-allegedly-behind-breach-of-south-korean-nuclear-institute/

- https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/14.%20FS-Decentralized-energy-system.pdf

- https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-02464-5

- https://www.energy.gov/articles/department-energy-statement-chinese-hacking-global-managed-service-providers

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2021/04/29/was-china-behind-last-octobers-power-outage-india-heres-what-we-know/

- https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2021/07/01/skepticism-to-acceptance-how-putins-views-on-climate-change-evolved-over-the-years-a74391

- https://www.e-ir.info/2020/02/24/the-energy-relationship-between-russia-and-the-european-union/

- https://www.vox.com/world/2018/3/28/17170612/russia-hacking-us-power-grid-nuclear-plants

- https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/13/13/7328/pdf

- https://www.jpost.com/middle-east/iran-news/iran-seeks-tech-in-sweden-for-nuclear-weapons-swedish-intel-report-666792

- https://www.manageengine.com/log-management/phishing-attacks/iranian-hackers-attack-uk-universities-email-phishing.html

- https://www.timesofisrael.com/after-alleged-iranian-cyberattack-israels-water-authority-beefs-up-defenses/

- https://time.com/4270728/iran-cyber-attack-dam-fbi/

- https://www.bbc.com/news/stories-57520169

- https://us-cert.cisa.gov/china

- https://www.fpri.org/article/2021/07/understanding-russias-cyber-strategy/

- https://www.csis.org/programs/technology-policy-program/publicly-reported-iranian-cyber-actions-2019

- https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2020/12/23/building-resilience-to-the-north-korean-cyber-threat-experts-discuss/

- https://bolddata.nl/en/companies/netherlands/energy-companies-netherlands/

- https://www.nwo.nl/en/key-enabling-technologies

- https://fd.nl/tech-en-innovatie/1414264/waterstof-zet-de-machtsverhoudingen-op-zijn-kop-psk1cajlBIZd

- https://www.wsj.com/articles/energy-tech-firm-hit-in-ransomware-attack-11620764034

- https://nos.nl/artikel/2415542-digitale-aanvallen-op-europese-olieterminals-ncsc-ziet-geen-verband

- https://spectrum.ieee.org/the-real-story-of-stuxnet

- https://edition.cnn.com/2021/07/23/tech/taiwan-china-cybersecurity-intl-hnk/index.html

- https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/ASPJ/journals/Volume-35_Issue-1/C-Ross.pdf

- https://www.cfr.org/blog/cyber-deterrence-dead-long-live-cyber-deterrence