- SERVICES

- THREATS

- Sector-based threat landscape

- Agriculture

- Energy

- Maritime

- Manufacturing

- Technology

- Logistics

- Governments

- Country threat profiles

- Russian Federation

- China

- Iran

- North Korea

- United States

- Israel

- Threat actor profiles

- Fancy Bear/APT28

- Cozy Bear/APT29

- OilRig/APT34

- Charming Kitten/APT35

- Lazarus/APT38

- Double Dragon/APT4

- Sandworm

- Seaturtle

- Silent Librarian

- RESOURCES

- ABOUT US

- CONTACT

Cyber Siege on the Fourth Estate: Protecting the Press

Our western democratic societies are built on independent legislative, executive, and judicial powers that need to be separated from each other. For them to function as intended, the public needs to have trust in these institutions. This can only be done through transparency and scrutiny, which leads to what is often considered to be the fourth pillar of our democratic societies: the press. But what happens to our society when the press and our media institutions are constantly being attacked and compromised in the digital domain?

Journalists and news media organizations are increasingly becoming targets of oppressive regimes and malicious threat actors often controlled by these states. Hunt & Hackett observes a growing cyber threat against news media, therefore this blog aims to provide further understanding of this escalating concern. The aim of these attackers has primarily been to gather intelligence, influence or disrupt. Such attacks on (news)media pose a direct threat to the effective functioning of democratic societies. Although the effects of sustained cyberattacks over a prolonged period of time are still unknown, it is nevertheless clear that it is of upmost importance to protect the integrity and independence of the press and media organisations.

Press and news media are currently not in great shape. They are struggling in their traditional roles as the providers and distributors of news and information to our society. In the current Information Age social media has taken some of their shine away as the role as disseminators of information to the public, opinion makers, and as watchdogs for holding the people in power accountable. With the rise and success of YouTube podcasts and news shows, donation based open news platforms such as Substack, or even just self-appointed Twitter-opinion makers, it is sometimes easy to forget that it is the press and their (investigative) journalism that provides the mirror to our societies. In some sense, the free press is now facing a “perfect storm.” Their position has been weakened by both social media, their business model has been disrupted by the erosion of paper-based news consumption, and at the same time geo-politics are back on the world stage. Threat actors are targeting both social and news media to gain influence or manipulate and disrupt the flow of information. Traditional news media organisations must tackle these increasing challenges from their weakened financial position. What is at stake, however, is far greater than the direct impact on the press and media organisations themselves. This is what we need to be vigilant about and develop a solution to help protect our free press and news media organisations in dealing with the increase in targeted attacks – and consequently to protect democracy.

-World Press Trends 2022

Trends

The last decade has shown not only increased cyberattacks against media organizations, but also personal attacks against journalists, such as doxing[1] and reoccurring source exposure scandals. This has resulted in newsrooms becoming more concerned about their information and cybersecurity standards, allocating more resources towards these areas. However, journalists and media organizations still tend to look at possible security measures from a reactive point of view, rather than taking a proactive, preventive approach.[2] The increased awareness does not seem to have a meaningful effect on the security of the media industry. According to a 2022 report from BlueVoyant, media firms are, on average, twice as susceptible to compromise than other sectors. An analysis of almost 500 companies found 30% active vulnerability exposures on media companies’ networks. However, since the analysis only took into account “internet-facing, publicly accessible” information, this number could be even higher. Furthermore, an astonishingly high 60% of identified vulnerabilities remained unpatched 6 weeks after discovery. However, this does not necessarily indicate a lack of care or interest, rather the complexity of media organizations’ digital supply chain from service providers and external sources to the user.[3] It also likely reflects the financial strain many of these organizations are under, given the difficulties associated with monetizing news in the age of social media and a shifting advertising landscape. Resource limitations may play a significant, although potentially under-recognized, role in the media industry’s vulnerability to cyberattacks.

Although cyberthreats have been present for decades, the pandemic rearranged the threat landscape. In early 2020, work-from-home orders were issued, and in a lot of cases it became an accepted way of working. Working from home, however, blurred the boundaries between work time and free time, and also between work and personal devices. Professional accounts are often used to logon on personal laptops and mobile phones, providing a wider attack surface for malicious actors. This is especially troubling in case of investigative journalists, who often interact with high-risk sources and possess confidential information.[4] What makes the targeting of news organizations and (investigative) journalists so attractive, particularly to state-sponsored Advanced Persistent Threat (APT) groups, is exactly the interconnected and sensitive nature of journalists’ digital presence. Journalists often possess critical political, financial or military-related information, have broad networks and connections to whistle-blowers and dissidents, and handle sensitive data on high-profile individuals. Accessing their networks or devices can therefore be a valuable information-gathering tool for state-sponsored or state-aligned APTs. Researchers at Proofpoint identified a sustained effort to compromise journalists’ networks in recent years. Some campaigns tend to align with political events, while others are reactionary when a media outlet publishes something deemed to be derogatory to the attackers’ nation.[5] Cyberattacks, however, can have a larger societal impact than just data breaches, information theft or financial loss; by intimidating journalists and restricting their ability to adequately conduct their investigations, the freedom of press itself may be in jeopardy. A 2022 World Press Trends survey found that cyberattacks are the single most common intimidation technique, experienced at least once by 45.7% of surveyed media organizations or their employees globally.[6]

MITRE Analysis

|

APTs |

99 |

|

Tools |

1.312 (1.077 unique) |

|

Techniques |

1.536 (328 unique) |

|

Origin Country |

China, Russia, Iran |

|

Motivation |

Espionage, Information Theft |

Figure 1 - The number of APTs, and the TTPs and Tools used in the media sector as observed by Hunt & Hackett.

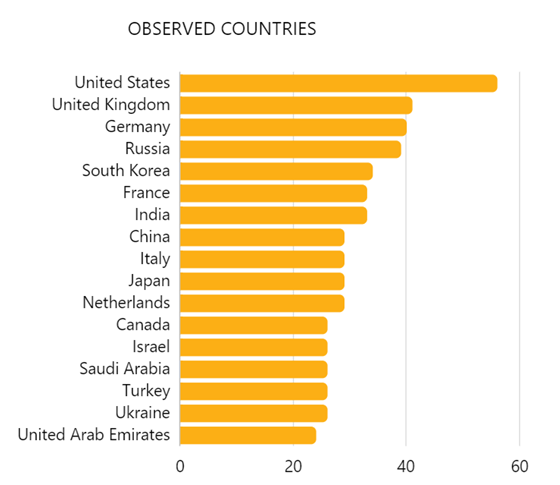

Hunt & Hackett is currently monitoring the activities of more than 500 APT (Advanced Persistent Threat) groups, 99 of which has been observed to have conducted cyberattacks against media outlets and journalists. Although there are examples of attacks before 2010, media institutions became heavily targeted during 2011-2012, and the rate of the attacks has been growing ever since. The majority of threat actors in the media sector’s threat landscape originate from China, Russia and Iran, and their most targeted countries are the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany and Russia. As of 2023, the Netherlands is the 11th most targeted country in the media sector. The motivation for these attacks is primarily espionage and information theft, however financial gain, destruction and sabotage are not unprecedented motives either. An important correlation observed is that the likelihood of media organizations being targeted increases in line with other industries. Attacks on governmental organizations, technology companies or the banking and investment sector all imply the heightened likelihood of attacks against the media and publishing sector.

Figure 2 - the most observed countries by APTs tracked by Hunt & Hackett

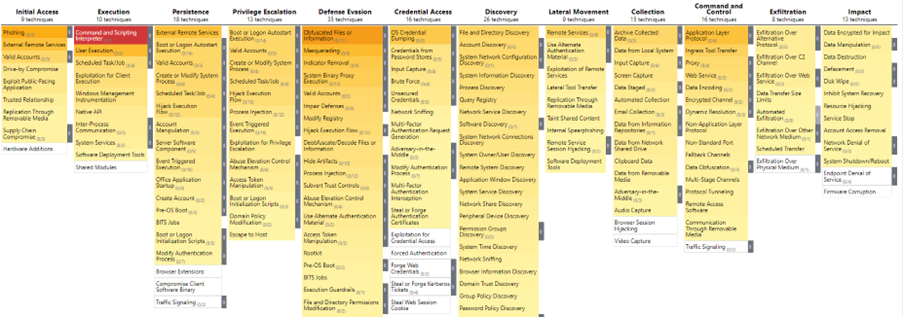

When it comes to the tools and techniques attackers use when targeting the media industry, there is unfortunately no set-in-stone procedure. There are multiple techniques in every phase of the attacks that can be used, contributing to the unpredictable nature of APTs. Nevertheless, there are some techniques that are more commonly used than others and therefore worth paying attention to. Initial access to the network or device is usually gained via Phishing (T1566). This often includes targeted spear phishing emails from impersonated or spoofed accounts, containing malicious attachments or links, but the use of social media such as LinkedIn or Twitter is increasingly popular as well. During the first phase of the attack, - which is called reconnaissance - it is common for the attackers to conduct in-depth research about the target before the initial contact, in order to get to know them and be able to gain trust. Aligning with phishing attacks in general, the single most used technique for the execution phase is by abusing a Command and Scripting Interpreter (T1059), such as JavaScript or PowerShell. The payloads are delivered through the attachments or links and can execute the arbitrary commands of the attackers on the victims’ machine. Lastly, the technique of Obfuscated Files or Information (T1027) is widely used by actors targeting journalists. This usually involves encrypting or encoding files in the network in order to evade defences.

Figure 3: Overview of the most used attacking techniques in the media sector

Threat Actors

Hunt & Hackett is actively monitoring almost a hundred APT groups who are known to have targeted media organizations or journalists. In order to understand the threat they pose, it is worth exploring some examples of groups and attacks in the cyber threat landscape.

A/ Gamaredon (aka Iron Tilden, Primitive Bear, Actinium, Armageddon, Shuckworm)

Gamaredon is a Russian APT group, active since 2013. Although they have targeted both public and private organizations in dozens of countries all over the world, their focus has shifted to Ukraine in recent years. They have been observed to turn from readily available tools to custom-developed malware which implies improved technical abilities and steady resources, although a direct link to Russian state agencies has not yet been definitely identified. The group is associated with the Pterodo backdoor as well.

Gamaredon has been targeting Ukrainian governmental and military agencies for some time, but the scope of their 2019 campaign expanded to include journalists as well. For instance, a data leak presumably against the Joint Forces Operation, which oversees journalists’ application to report in combat zones, resulted in dozens of journalists receiving text messages threatening them with 10 years of prison for “genocide and prohibited means/methods of warfare.” In a social media post, Kyiv Post journalist Anna Myronyuk stated: “I will be happy to make a mistake, but so far everything looks different – that it is not becoming safer to work as a journalist in Ukraine.”[7] This operation is suspected to have been carried out by Gamaredon.

According to Hunt & Hackett’s monitoring of the group, they have been getting increasingly active, with early 2022 seeing the most Gamaredon activity. This is in line with the timeline of the Russian war against Ukraine. Their main motivations are espionage and information theft, and their primary targets are governmental and defence institutions, NGOs and the media sector. Their most used techniques during attacks are Command and Scripting Interpreter (T1059), Obfuscated Files or Information (T1027), and System Binary Proxy Execution (T1218).

At the same time, however, Gamaredon has been observed to change their TTPs (tactics, techniques and procedures) during their latest campaigns. They regularly make use of phishing emails, html attachments, Telegram messenger to identify IP addresses for Command and Control, and various DNS related techniques.[8]

B/ TA459

Compared to Gamaredon, relatively little is known about the Chinese group TA459. They are a newer actor on the cyber playing field, the first documented attacks dating back to early 2017. They are motivated by espionage and information theft, with attacks identified in Belarus, Russia, Mongolia and some Southeast-Asian regions. Their main target sectors include financial, banking and investment services, political agencies, and they also focus heavily on journalists, media industries and telecommunication companies.

A noteworthy attack against media personnel took place in early 2022. Although the specific identities of the victims are not known, according to Proofpoint they were responsible for reporting on the Russia-Ukraine war. This is in line with their past activities focusing on Russia-related intelligence. During the 2022 campaigns, victims received phishing emails with malicious attachments. The emails originated from a legitimate but spoofed Pakistani government email address. The malware with which the attackers gained persistence in the victim’s network is Chinoxy, a backdoor that has been in use since 2018.[9]

TA459 has used Command and Scripting Interpreter (T1059), Exploitation for Client Execution (T1203), Spearphishing with Attachment (T1566.001), and User Execution: Malicious File (T1204) most often. In 2017, they were observed to exploit the CVE-2017-0199 zero-day vulnerability to install the PlugX Remote Access Trojan. Additionally, their toolkit also contains the NetTraveler spyware and ZeroT trojan malware.[10]

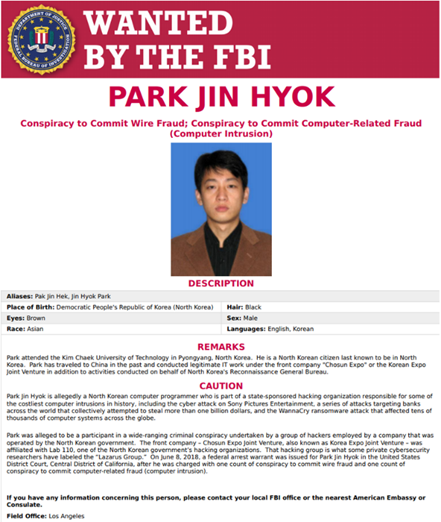

C/ Lazarus

Lazarus or APT38 is a notorious North-Korean state-run APT group suspected to be active since 2007, with their first confirmed attacks in 2009.[11] A North-Korean defector claims that the group, known in the country as the 414 Liaison Office, has a direct telephone connection to Kim Jong-un.[12] Their targets include most North American, European and East-Asian nations, and although their main motivation is espionage and information theft, they have been observed to conduct attacks for financial gain, sabotage and destruction as well. They are somewhat indiscriminate in the sectors they target as long as the attacks align with North-Korea’s political aims. They have carried out campaigns against the public sector, with targets including governmental or defence institutions, but also technology companies, businesses operating in the logistics sector, financial institutions, BitCoin exchange servers, and the media and publishing industry.

In 2014, an attack carried out by Lazarus against Sony Pictures entertainment resulted in a large-scale data breach, with huge amounts of data including unreleased movies and personal employee information leaked to the public.[13] It is believed that the attacks were at least partially motivated by the upcoming comedy movie about Kim Jong-un. Although unconfirmed, this aligns with the group’s ideological convictions, while demonstrating their danger and capabilities. In 2022, US-based journalists were targeted with highly customized phishing emails after the publication of an article critical of the North-Korean leader.[14] These attacks were a part of Operation Dream Job, a job application themed campaign against media and IT companies, affecting over 250 people.[15] Targets received highly customized emails containing malicious links to attacker-owned, fake websites imitating well-known job-hunting pages such as Indeed and ZipRecruiter. Although this campaign was not successful, it confirms that Lazarus is an active threat actor for the media sector.

Figure 1: One of the members of the infamous Lazarus Group, wanted by the FBI | Source: FBI

The group has a wide repertoire of tools and techniques, but some are more commonly used than others. Lazarus has been observed to regularly use Phishing (T1566), Command and Scripting Interpreter (T1059), Indicator Removal (T1070), System Binary Proxy Execution (T1218), Masquerading (T1036) and Obfuscated Files For Information (T1027).

Although these actors only represent a small fraction of all APT groups, general motivations to target journalists and media institutions are seen, and they also provide a window into how the attacks are carried out.

Known Attacks

Not all attacks have been successfully attributed to specific actors. Therefore, limiting one’s focus to known adversaries runs the risk of overlooking certain attack characteristics. The following examples highlight the diverse range of cyberattacks targeting media organizations and individual journalists.

- In August 2012, Reuters reported that their blogging platform had been hacked. Attackers posted false articles, including an interview with the head of the Free Syrian Army. In this interview false claims were made about the FSA’s position and strategy, presumably aiming to cause confusion on the frontlines.[16] The attackers were never identified, but the political motivation behind the incident is clear. Coincidentally – or not? – the same day that Reuters reported about the attack, Wired journalist Mat Honan experienced a complete overtake of his digital existence. His Google, Twitter and AppleID accounts were infiltrated, giving the attackers access to years’ worth of personal as well as professional data. The attackers proceeded to send out racist and homophobic tweets, deleted his Google account and wiped his iPhone. Honan later learned that the attackers gained access to his accounts by social engineering, specifically by tricking Apple and Amazon tech support services by providing information such as partial credit card numbers that they gathered from different call centres. Other than the security flaws in the respective service providers, Honan acknowledged his own contribution to the attacks by using weak, similar passwords to his different accounts, and not using multiple factor authentication. It is safe to assume that Honan was aware of the heightened risk by ignoring these basic safety measures, which is a common occurrence. This is why not only awareness but actual implementation should be encouraged more widely.

The journalist later got in contact with one of the attackers who goes by Phobia. He claimed to be 19 years old and admitted that his actions were largely motivated by the will “to get it out there to other people so eventually every1 can overcome hackers.”[17] As Honan decided not to file charges against the attackers, they have never been identified. It is, however, clear that private persons acting of their own accord can cause just as much damage to the individual as organized state-sponsored groups.

|

For sale: the (almost perfect) spyware Pegasus |

|

In 2021, Amnesty International went public with the news that they uncovered a highly sophisticated kind of spyware for mobile phones that was made and sold by the Israeli company NSO Group. The firm made use of a zero-day vulnerability in mobile phone software, which they weaponized by developing Pegasus. After discovering that they themselves had been hacked, Amnesty identified around 600 domain names used by clients of the NSO Group, which allowed them to get a grasp on the full scope of the deployment of this spyware and its targets. Activists, journalists, and political leaders were targeted with Pegasus. The attackers could practically take over the entire phone, gaining access to photos, contacts, messages and even the camera. At least 180 journalists in 20 countries were targeted. A chilling example, showing the shady nature of the spyware and its users, is that family members of journalist Jamal Khashoggi were targeted shortly before his murder in the Saudi Arabian embassy in Turkey in 2018. The malware was highly sophisticated and hard to detect. For example, the malware had a ‘zero-click’ feature, which allowed it to install itself on the device, without the actual user having to click a link. Since the discovery of the NSO spyware forensic tools have been made open source, allowing for easier detection. NSO maintains that they supply their technology only to “authorized governments [by the Israeli state] to help them fight terror and crime.” [18] Not just oppressive regimes haven shown an interest in the services of the NSO Group. In 2021, an NSO executive stated that over 5 European member states had purchased Pegasus.[19] The news emerged some time later that also the AIVD, the Dutch general intelligence service, had made use of the controversial software to track the infamous organised crime leader, drug lord and suspected murderer Ridouan Taghi.[20] |

- In January 2013, the New York Times became a victim of attacks originating from China. Although the attacks are not attributed to a specific actor, Mandiant alleged their ties to the Chinese military. During the attack, which started with malware being delivered via spear phishing emails, 53 employees’ computers were accessed. The incident was likely triggered by a series of stories run by the NYT about the excessive wealth of outgoing head of state, Wen Jiabao. The attackers were reportedly mostly interested in David Barboza’s email correspondence, who authored the exposé.[21]

As seen in the attacks described above, adversaries have been actively looking to compromise journalists’ accounts and media companies’ networks for more than a decade. However, it would be ill-advised to believe that this behaviour is in the past. In 2021 Qatar-based news network Al Jazeera reported a three-day period of continuous attempts to “access, disrupt and control” their websites. The network claims that the attacks were unsuccessful, and they have only increased “Al Jazeera’s resolve to continue its bold and exemplary journalism.” Not much is known about the attack patterns or who is behind them, but the news outlet often reports on political and military events in the Middle East which could serve as a probable motivation for foreign cyberespionage groups.

- In early 2022 News Corp announced its own security struggles. What has been identified as Chinese state-affiliated actors targeted journalists from The Times and Wall Street Journal – both belonging to News Corp – and stole a large amount of data. It is believed that the attackers were present in the network for much longer than expected, and they seemed to have focussed their efforts on information surrounding Taiwan, Uyghur Muslims, and President Biden and Kamala Harris. The Tech Monitor reported that this campaign was likely only a small portion of the - at the time - ongoing and intensifying hostilities in the cyber space between the US and China.[22]

- Individual journalists are still targeted as well. In April 2023 Matt Walsh, a controversial conservative commentator based in the US, suffered an attack on his accounts similar to Honan’s 2012 incident. Although not much has been reported on the issue, it is confirmed that the attackers used what is known a SIM swap scam to gain access to Walsh’s accounts. This technique exploits a weakness of two-factor authentication. The alleged hacker told Wired his motivation was simply to “stir up some drama” on Twitter.[23] He was successful.

The examples above demonstrate the broad range of attack types as well as motivations behind the threats media organizations and journalists face. When it comes to cyber incidents, most people think of financial loss, data breaches or deprived access to accounts. This is not only inconvenient but can have serious future implications such as bankruptcy, legal troubles, or reputation damage.

Conclusions

Based on the attacks and actors Hunt & Hackett is monitoring it can be derived that both organised state-sponsored groups and bored teenagers constitute a huge danger to journalists, who often possess very public profiles but have minimal knowledge of cybersecurity. As revelations related to the Pegasus project have demonstrated, journalist all over the world are a target of governments with questionable intent. Strict cyber-hygiene and the implementation of at least basic safety measures are advised for all that are active in the media industry, especially when dealing with sensitive information.

Attackers' motivations can also vary from destruction, information theft, or espionage, as highlighted by the examples provided in this article. It is important to note, however, that these examples are not exhaustive and serve merely as a glimpse into the possible attack types that adversaries may carry out. The threat is ever evolving, and staying up-to-speed is a challenge. In this age of political turmoil, geopolitical conflicts, and nearly ideal circumstances for nation-state hackers to thrive in, further attacks are anticipated.

The presence of a free and independent media is a vital pillar in Western democracies. However, when media organizations are unable to ensure the necessary security measures for data integrity and protected communication, there is a substantial risk. The potential impact on society extends beyond the security risks faced by media organizations themselves. Potential long-term consequences are too great for security not to become an upmost priority. It is imperative that we collectively seek new methods to safeguard and fortify this sector.

In an increasingly digital world, the cyber threat to journalists and media organizations is likely to escalate further. As technology advances and more information is exchanged online, the risks faced by journalists will continue to grow. It is crucial for individuals and organizations in the media industry to remain vigilant and adapt to evolving cybersecurity challenges to safeguard their operations and protect sensitive information. A good starting point is to become aware of spear-phishing, a technique often used in the media sector by malicious actors. Recently, Hunt & Hackett security experts published a blog providing more details and recommendations to counter this threat. Read more about spear-phishing on our website.

Sources:

[1] Doxing definition: the action of finding or publishing private information about someone on the internet without their permission, especially in a way that reveals their name, address, etc. Cambridge Online Dictionary

[2] The Rise of the Security Champion: Beta-testing Newsroom Security Cultures - Columbia Journalism Review (cjr.org)

[3] Media Firms Twice as Exposed to Compromise - Infosecurity Magazine (infosecurity-magazine.com)

[4] UNESCO - Threats that Silence: Trends in the Safety of Journalist (2021)

[5] Above the Fold and in Your Inbox: Tracing State-Aligned Activity Targeting Journalists, Media | Proofpoint US

[6] Challenges to Press Freedom: WAN-IFRA World Press Trends 2021–22 | by Damian Radcliffe | Damian Radcliffe | Medium

[7] Журналісти Kyiv Post поскаржилися на погрози з боку бойовиків ОРЛО, припустивши витік даних - Детектор медіа. (detector.media)

[8] Russian APT Gamaredon Changes Tactics in Attacks Targeting Ukraine - SecurityWeek

[9] Above the Fold and in Your Inbox: Tracing State-Aligned Activity Targeting Journalists, Media | Proofpoint US

[10] TA459, Group G0062 | MITRE ATT&CK®

[11] Lazarus Group, Labyrinth Chollima, HIDDEN COBRA, Guardians of Peace, ZINC, NICKEL ACADEMY, Group G0032 | MITRE ATT&CK®

[12] Drugs, arms, and terror: A high-profile defector on Kim's North Korea - BBC News

[13] A Breakdown and Analysis of the December, 2014 Sony Hack (archive.org)

[14] Above the Fold and in Your Inbox: Tracing State-Aligned Activity Targeting Journalists, Media | Proofpoint US

[15] Countering threats from North Korea (blog.google)

[16] Reuters blogging platform hacked, false Syria blog posted | Reuters

[17] How Apple and Amazon Security Flaws Led to My Epic Hacking | WIRED

[18] The Pegasus Project: How Amnesty Tech uncovered the spyware scandal – new video - Amnesty International

[19] NSO claims 'more than 5' EU states used its Pegasus spyware • The Register

[20] AIVD gebruikt omstreden Israëlische hacksoftware | De Volkskrant

[21] New York Times claims Chinese hackers hijacked its systems | New York Times | The Guardian

[22] US China cyber tensions highlighted in News Corp breach - Tech Monitor

[23] Matt Walsh's Twitter Hacker: I Was Just 'Stirring Up Some Drama' (gizmodo.com)

Questions, concerns or feedback?